by Kerry SHERIDAN

Agence France-Presse

TAMPA, United States (APF) – Researchers have found a new way that global warming is bad for the planet: more hungry bugs.

Rising temperatures will stimulate insects’ appetites — and make some prone to reproducing more quickly — spelling danger for key staples like wheat, corn and rice which feed billions of people, researchers said Thursday.

And since these three crops account for 42 percent of the calories people eat worldwide, any uptick in scarcity could give rise to food insecurity and conflict, particularly in poorer parts of the globe.

“When it gets warmer, pest metabolism increases,” said Scott Merrill, a researcher at the University of Vermont and co-author of the study in the journal Science.

“And when pest metabolism increases, insect pests eat more food, which is not good for crops.”

Prior studies have already warned of climate change’s harmful effects on food staples, whether by making water scarce for irrigation or sapping nutritious content from cereal grains.

The latest study adds to that body of research by focusing on the boosted appetites of pests like aphids and borers.

To find out just how bad it could get, researchers ran simulations to track temperature-driven changes in metabolism and growth rates for 38 insect species from different latitudes.

Results varied by region, with cooler zones more likely to see a boost in voracious pests, and tropical areas expected to see some relief.

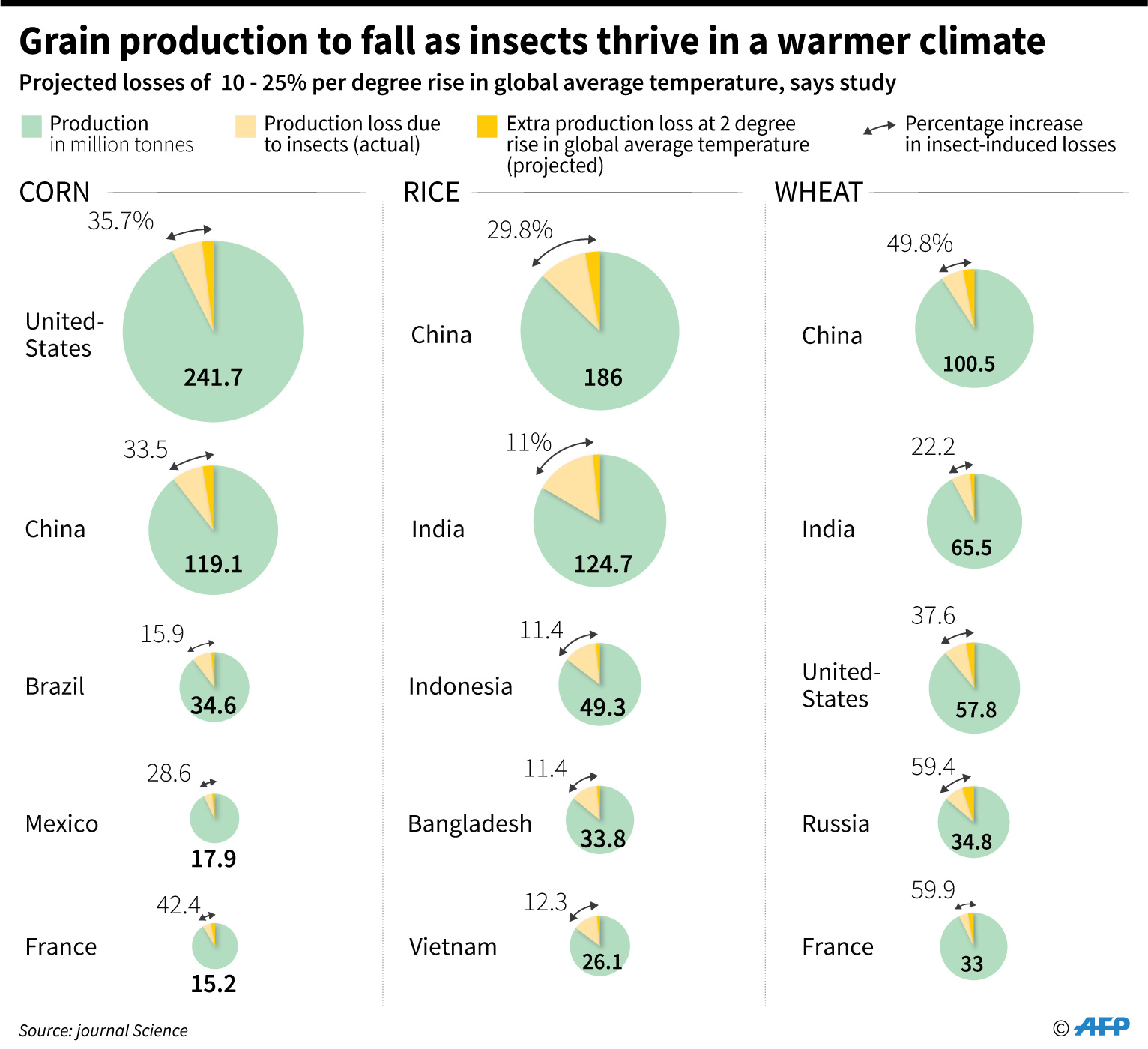

Overall, “global yield losses of these grains are projected to increase by 10 to 25 percent per degree of global mean surface warming,” said the report.

“In France or the northern United States, most of those insects will have a faster population growth if the temperature warms up a bit,” lead author Curtis Deutsch told AFP.

“In Brazil or Vietnam or a very warm place, then it might be the opposite,” said Deutsch, a researcher at the University of Washington.

France stands to lose about 9.4 percent of its maize to pests in a world that is 2 C warmer, compared to about 6.6 percent of yield losses today due to pests.

In Europe, currently the most productive wheat producing region in the world, annual pest-induced yield losses could reach 16 million tons.

Eleven European countries are predicted to see 75 percent or higher losses in wheat from pests, compared to current pest damage.

In the United States, the world’s largest maize producer, insect-induced maize losses could rise 40 percent under current climate warming trajectories, meaning 20 fewer tons of maize per year.

China, home to one-third of the world’s rice production, could see losses of 27 million tons annually.

The study did not account for any anticipated increase in pesticide use, or other methods of stemming the expected crop loss.

– ‘Insane’ aphid population –

Consider the case of a particularly dangerous pest, the Russian wheat aphid.

Though tiny, these bugs are a major threat in North America, where they are considered an invasive species after first being detected in the 1980s.

Merrill said no aphid males have been found in Canada or the United States. The females, it seems, are reproducing clonally, essentially “giving birth to live clones of themselves,” he told AFP.

“These insects are born alive. They are born pregnant. Not only that, their granddaughters are developing inside them when they are born. It is crazy,” he added.

“They can reproduce under ideal temperatures very quickly,” on the order of eight daughters a day.

“You can imagine how quicky a very small population, even one aphid, can just explode over a whole field season. One or two aphids could turn into a trillion under ideal conditions. It is insane how quickly these populations could grow.”

Until now, most research on crop effects from global warming has focused on the plants themselves.

But researchers hope their findings will spark a hunt for more local solutions, like selecting heat and pest resistant crops and rotating plantings rather than simply dumping more pesticides into the environment.

“We have to start thinking about how are we going to short-circuit some of those things before they actually happen,” Merrill said.