By Rommel B. David

It was 11:30am. Passengers were rushing to and from the port area of Allen in Northern Samar in Eastern Visayas. We were among the people at the port entrance. The sweltering temperature coming from the sea doubled the scorching heat of the sun. The humid air dampened our skin while the rays of the sun blinded our eyes. The heat made it difficult to use the improvised ladder to disembark from our dancing, wave-tossed boat. As I tried to use the ladder, I realized I had a problem. I forgot my slippers and for sure, I will have to use slippers because we are going to shoot in the seashore. I could not afford to get my street shoes wet. This was nothing, however, compared with my bigger work concerns at that very moment.

I needed a story, a compelling story, because the stories in our itinerary weren’t feasible and strong enough to stand for broadcast. I badly needed a miracle.

“You need to find the miracle, it will not chase you,” these were the words I whispered to myself as I continued to search for the cheapest pair of slippers in the stores 10 meters from the boat. While choosing what to buy, I was asking the vendors if they know kids diving for “tuna.”

“Bawal na ‘yan dito sir! (It’s not allowed here, Sir!),” they said. “Pero kung gusto mo, may sisid barya dito.” (But if you like, there are kids here diving for coins.)

It didn’t come to me until they showed me a group of kids. They were all boys. They were running out of breath after long dives in waters 12 feet deep. The smallest of them was nine while the tallest was fifteen. The middle one was eleven. They were small for their age. Their skin was darkened by the sun. They were siblings.

(Photo owned by Rommel David.)

They were hugging their bare bodies while water dripped from their shorts. I could see their bones through their dry, pale skin. Their lips were colorless.

And then the middle boy started to ask me, “Sir pahagis ng barya! Sige na! Magda-dive ako. Pang-kain lang namin.” (Sir, throw some coins! Please! I will dive for it! We need to eat.)

I was deeply saddened; I wanted to give all the coins left in my purse. But still, it would be just be an immediate and temporary solution. Because I know, the problem is not just them being hungry at that moment – it was the day-to-day hunger that made them malnourished and sickly.

For scientists at the International Rice Research Institute, the “super rice” project will save these kids and those two billion more around the globe who suffer from the same plight: “hidden hunger” or iron deficiency. But they are not all children. In the Philippines, 43% of the total population who have iron deficiency anemia (IDA) are pregnant women while 33% are elderly.

“Our main thrust is to develop rice which is going to be healthier because we add micronutrients which has been identified as lacking in regular rice we are eating now.

So far, the nutrients we identified are vitamin A, zinc, iron and folic acid,” said Dr. Jessica Rey, postdoctoral fellow working on the project at IRRI. However, they are focusing on iron because iron deficiency is the most pervasive form of malnutrition worldwide.

The “super rice” project of IRRI aims to develop high-iron rice to alleviate iron-deficiency anemia or IDA.

The iron-rich rice project

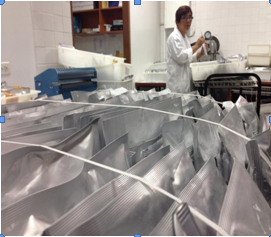

The project has been in the laboratory since 2002 when a group of Catholic nuns underwent a double-blind experiment to test if bio-fortified rice was effective. The case studies were all women of childbearing age sharing a common kitchen, and according to the researchers, “they were very cooperative.”

A study was published in 2005 in “The Journal of Nutrition” and discussed the said experiment:

“192 Catholic religious sisters in 10 convents took part, eating only the experimental rice which contains four to five times more iron than commercially available rice in the Philippines. After nine months, blood samples showed the iron status of the sisters was 20 percent higher than women who ate the traditional rice.”

Simply put, the higher iron in the rice was absorbed by the nuns involved in the experiment.

But these participants were more fortunate than the mother of the boys we met in the port area of Allen. The nuns had a healthier kitchen and ate three times a day. In contrast, the mother of the young “coin divers” was obviously undernourished, barely eating a complete meal in a day. She also obviously lacked a suitable kitchen in their cramped house where the kitchen and dining area also doubled as a living area.

When we visited their house, Josephine, the boys’ 35-year old mother, was swaying her two-month old undernourished baby in her arms, while shouting at her two other children playing in the kitchen cum living room area. Adjacent to the living room was the bedroom, where the entire family of eight slept.

“Naghihintay ng biyaya (Waiting for blessings),” Josephine said, while peeling unripe mangos that they would share for lunch. The family had coffee for breakfast.

The children arrived, a handful of coins tinkling in the pockets of their shorts. They gave their hard-earned money to their mother .

“Pambiling bigas e kulang naman ‘to kahit sa 1/4. Konti lang ang kanilang ano 13 pesos. E ano lugaw na lang ‘to. Maglulugaw kami 1/4. Wala na kasi kaming pangdagdag diyan.”

(We will buy rice but only 1/4 kilo, thirteen pesos. We will just cook porridge. We don’t have any more money to add.)

Pushing for hope

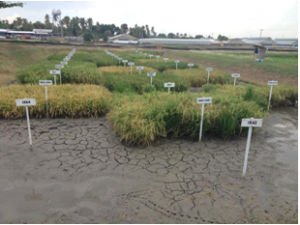

This scenario represents the reason for scientists at IRRI to keep on pursuing research and field trials. For 12 years, they have worked on discovering the right varieties of rice to use and breed.

“The countries we target are the poorest of the poor like Bangladesh and Philippines. Go to them, have lunch with them, they have rice and salt only or rice and coffee,” Dr. Rey said.

This is actually no different from the real situation of families in the Philippines like that of Josephine.

This year, IRRI scientists are still working in research and development, and they can only go as far as testing different rice varieties in the laboratory and in a confined field.

Dr. Reyes explained their work . “We encourage the rice plant to absorb more iron from the soil, take it all up, and distribute it inside the plant. This falls under the process of biofortification.”

The idea of biofortification is to breed crops to attain high nutritional value. IRRI scientists looked for a rice variety that is naturally high in nutrients and bred this so it could turn into a new high-yielding “iron-rich” miracle rice variety..

High iron rice by 2029?

IRRI expects to finish the variety breeding phase by 2018.

“We don’t have a deadline but we have a target. We have a realistic timeline. Within three years, these are things we are going to do. If it will be okay, we move to other parts,” Dr Reyes said.

IRRI needs another 15 years for them to complete the project: field testing the varieties in different locations, evaluating safety of the rice, making it available in the market for planting, and making it consumable.

“We are very positive with that. They are waiting for our success,” she added.

But by that time, the oldest of the coin divers we had earlier interviewed, would have turned 30-years old already. In rural areas, men of that age already have a family and plenty of kids

In that case, he will be facing the same dilemma: he will be employed as a construction worker like his father, his kids will be coin divers too, and it will still be hard for them to bring food to the table.

Even Dr. Rey commented on the tedious process of rice science research. “Baka retired na ako ‘pag na-develop ito. Baka hindi na lang itong iron ang kailangan ko.”

(Maybe I’m already retired after this project succeeds. And maybe iron is not the only nutrient I need.)

“Work never ends. It’s just our enthusiasm and energy. Luckily, a lot of people still trust IRRI and continue supporting us,” she said.

IRRI aims to release the would-be crop for “free” first in the Visayas, where Josephine’s family lives. If this miracle will happen in 2029, poor families like Josephine’s will not only have free rice on their plate but will also enjoy healthier rice.

As we left Josephine and her kids in their house, they were enjoying the porridge she cooked for the children.

“Masarap kumain kapag may pagkain” (It’s good to eat if there’s food to eat), her youngest son said, as he tipped the bowl to his mouth to get to the last drop of the porridge.

(The author is taking up M.A. Journalism under the Konrad Adenauer Asian Center for Journalism in Ateneo de Manila University.)