by Marlowe HOOD

Agence France-Presse

PARIS, France (AFP) — The kilometres-thick icesheet that covers Greenland saw a near-record imbalance last year between new snowfall and the discharge of meltwater and ice into the ocean, scientists have reported.

A net loss of 600 billion tonnes was enough to raise the global watermark 1.5 millimetres, about 40 percent of total sea level rise in 2019.

The Greenland icesheet — which, until the end of the 20th century accumulated as much mass as it shed — holds enough frozen water to lift the world’s oceans by seven metres.

Almost as alarming, however, as the icesheet’s accelerating disintegration are the forces driving it, the authors reported this week in The Cryosphere, a peer-reviewed journal published by the European Geosciences Union.

More than half the dramatic loss in 2019 was due not to warmer-than-average air temperatures but rather unusual high-pressure weather systems linked to global warming.

These anticyclone conditions blocked the formation of clouds over southern Greenland, causing unfiltered sunlight to melt the icesheet surface. Fewer clouds also meant less snow — 100 billion tons below the 1980-1999 average.

In addition, the lack of snowfall left exposed darkened, soot-covered ice which absorbs heat rather than reflecting it, as pristine white snow does.

Conditions were different, but no better in the northern and western parts of Greenland, due to warm, moist air pulled up from lower latitudes, the study showed.

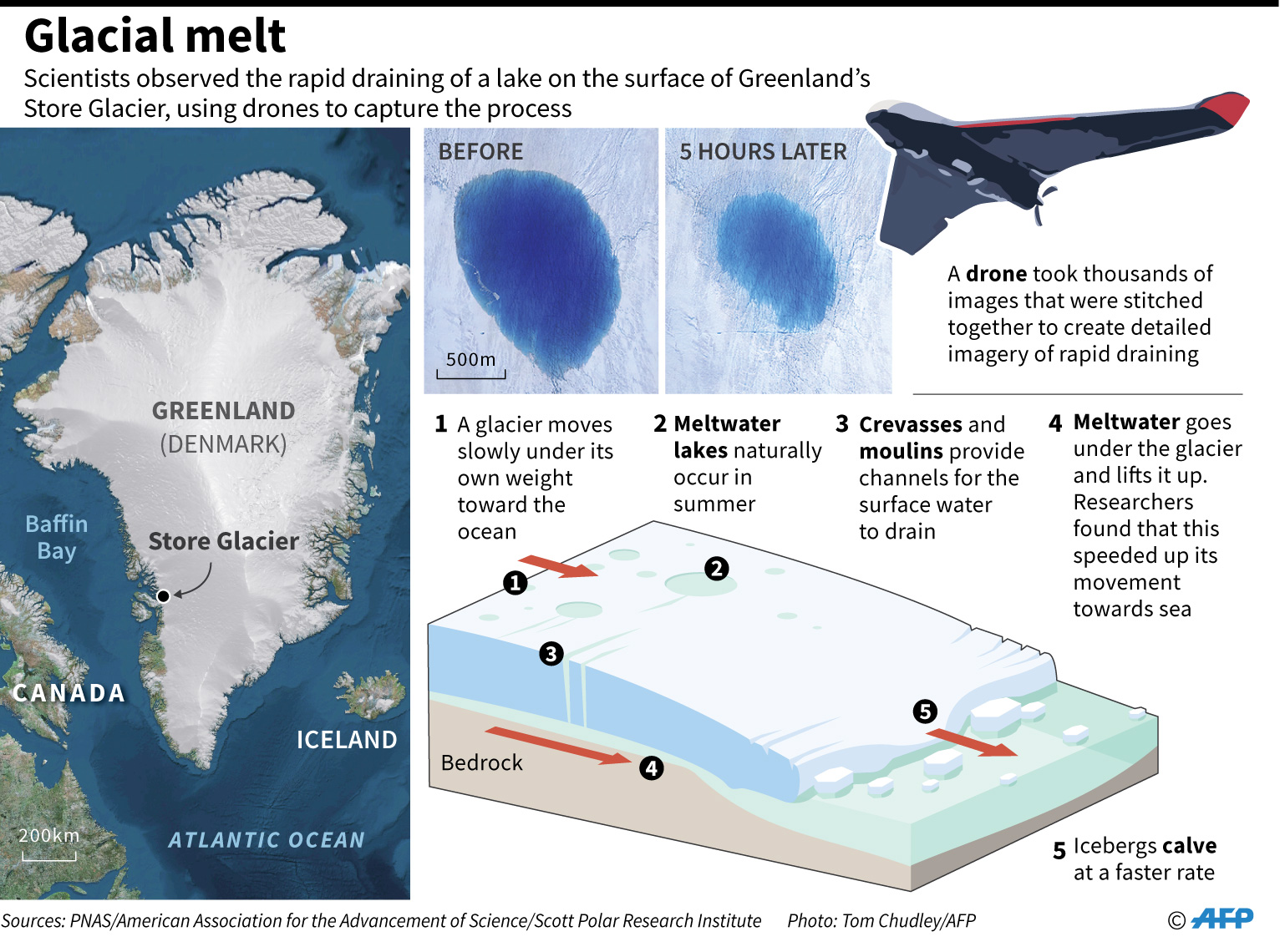

All of these factors led to accelerated melting and runoff, creating torrential rivers cutting through the ice toward the sea.

“These atmospheric conditions are becoming more and more frequent over the past few decades,” said lead author Marco Tedesco, a scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

“This is very likely due to the ‘waviness’ in the jet stream,” a powerful, high-altitude ribbon of wind moving from west to east over the polar region, he said.

Twice the global average

The disruption of the jet stream’s normal patterns have been linked to the disappearance of sea ice, the faster rate of atmospheric warming in the Arctic, and disappearing snow cover in Siberia — all consequences of global warming.

Average temperatures in the Arctic region have risen two degrees Celsius since the mid-19th century, twice the global average.

“Climate change, in other words, may make the destructive high-pressure atmospheric conditions more common over Greenland,” Tedesco said.

Indeed, 2019 is not the first time that such anomalies have emerged, with more than half the years this century showing similar, if less pronounced, patterns.

The impact of these high-pressure systems are not factored into climate models used by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to project the impact of global warming on the Greenland icesheet, the study warns.

“It is likely that we are underestimating the future melting by a factor of two,” co-author Xavier Fettweis, a research associate in the Climatology Laboratory at the University of Liege in Belgium, told AFP.

The new study attributes nearly 70 percent of the meltwater runoff and iceberg discharge last year to the high pressure systems, and the rest to direct warming of the atmosphere under climate change.

The discharge last year was comparable to the record year 2012, but air temperatures in 2019 were significantly lower.

Through the 1990s, the Greenland ice sheet was roughly in a state of balance, but annual mass loss has risen since then.

In all, Greenland has shed about four trillion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2018, causing the mean sea level to rise by 11 millimetres, according to a study in December 2019 study in Nature.

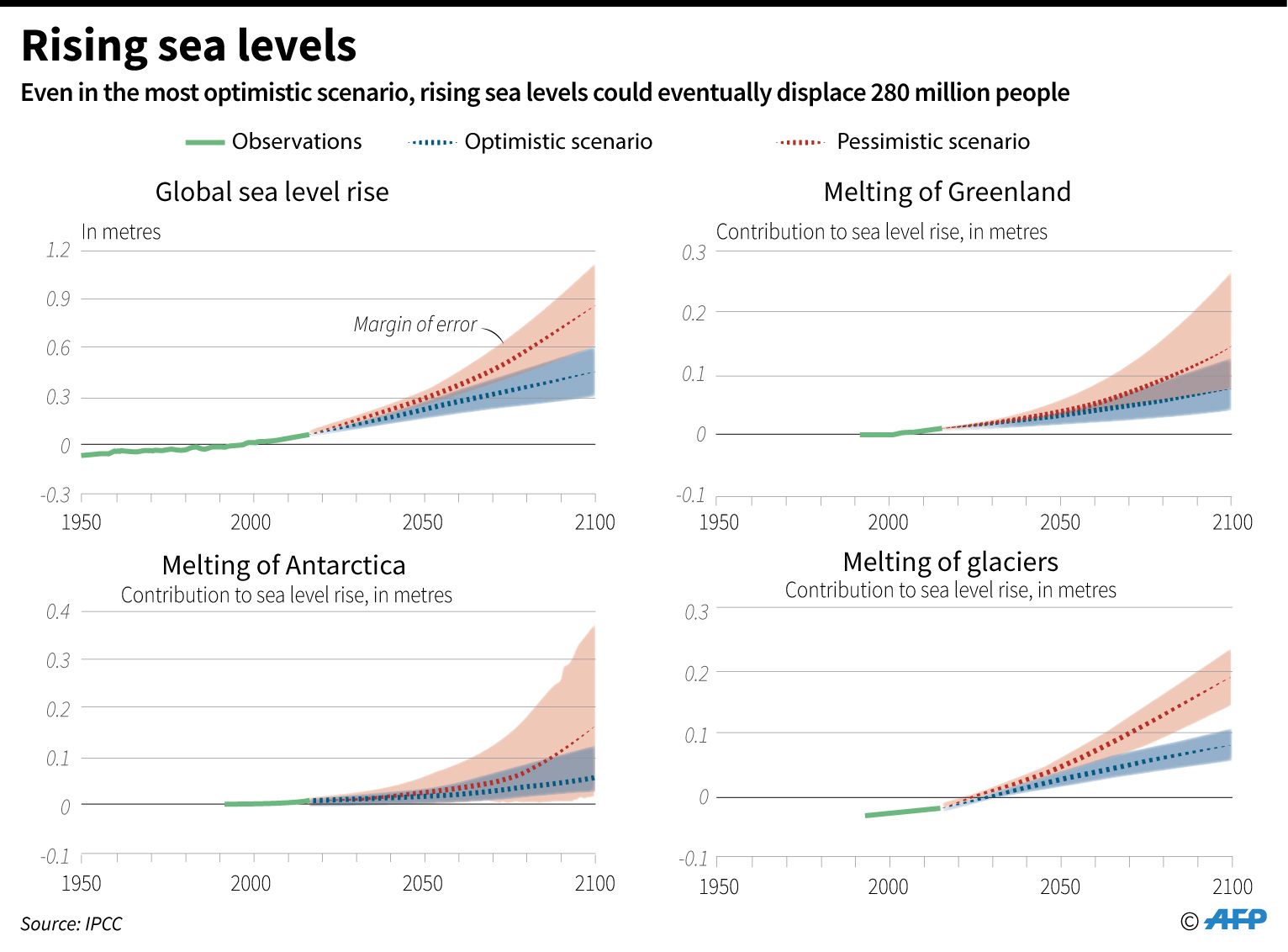

The IPCC has forecast that global sea level rise could top a metre by 2100, due mostly to discharge from the icesheets on Greenland and West Antarctica.

© Agence France-Presse