by Eugenia LOGIURATTO

Agence France-Presse

PORTO JOFRE, Brazil (AFP) — Lieutenant Silva’s face is grim as he watches his firefighters try — and fail — to control one of the thousands of wildfires ravaging Brazil’s Pantanal, the world’s biggest tropical wetlands.

“It needs to rain. We’ve got low moisture, intense heat. With that combination, rain is our only hope,” says Silva, even as new flames break out at the spot his team of six firefighters is trying to douse on the grounds of an ecotourism hotel in the northern Pantanal.

Even when the fire looks to be out, embers continue burning underground, feeding on layers of dry leaves that have accumulated amid the region’s worst drought in nearly five decades.

The firefighters advance about 60 meters (yards) into a dense patch of charred scrubland, but the hoses connected to their truck can reach no farther.

One starts using a leaf blower to clear away the dead vegetation, which momentarily extinguishes the flames on the surface.

But the slightest gust of wind is enough to reignite them.

Silva decides to retreat and change tactics: better to create a fire break by soaking the ground around the truck in water.

The firefighters hope that will prevent the flames from reaching the other side, where there is a still intact hill of native vegetation inhabited by jaguars.

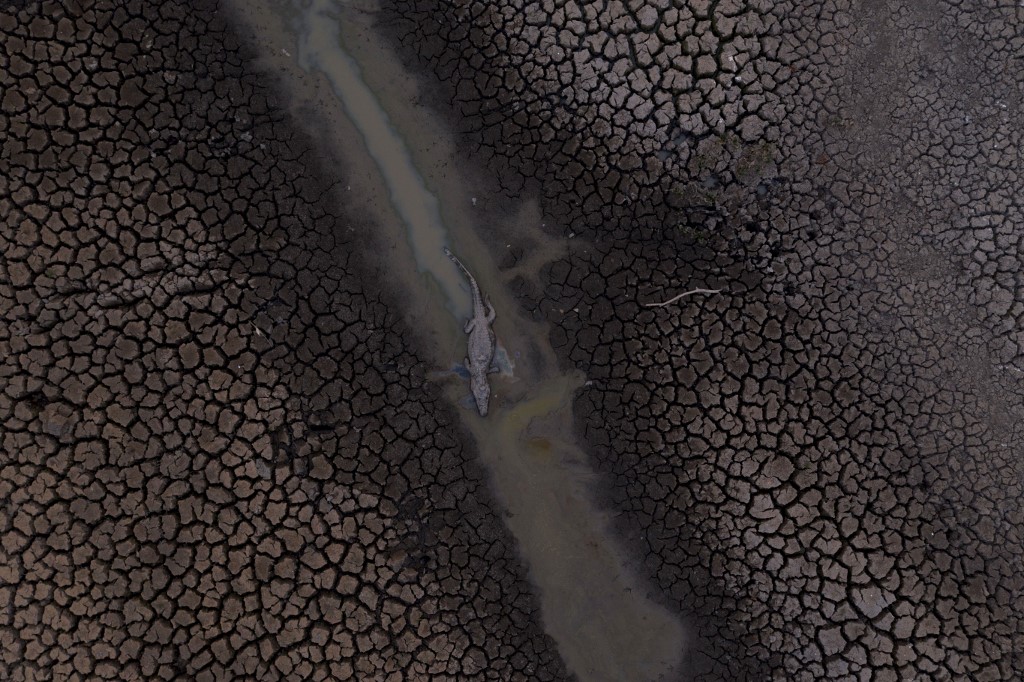

The Pantanal sits at the southern edge of the Amazon rainforest, stretching from Brazil into Bolivia and Paraguay.

The region is known for its lush landscapes and biodiversity.

But this year, some 23,500 square kilometers (9,000 square miles) of the wetlands have gone up in smoke — nearly 12 percent of the Pantanal.

Helped by local volunteers, firefighters are racing to control the flames before they destroy the area’s hotels and numerous wooden bridges, essential infrastructure for getting in and out of a region normally covered in water this time of year.

Hotel worker Antonio da Silva is one of the volunteers helping safeguard the bridges, wearing a cowboy hat and face mask.

“I’m from this region, I’ve lived in the Pantanal for 60 years, and I’ve never seen anything like this,” he says.

© Agence France-Presse