By Bahira Amin

At the foot of an 800-year-old Cairo mausoleum, weeds rise from a murky green pool — a sign of massive loss of clean water that often goes to waste instead of reaching Egyptian consumers.

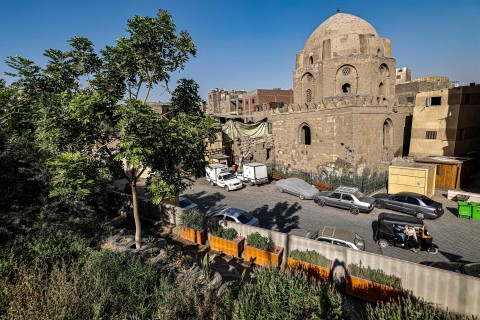

Beneath intricate Koranic inscriptions, the thick shrubbery crawls upwards from waist-deep water towards the 13th-century Al-Ashraf Khalil dome in the Egyptian capital’s historic quarter.

But “it’s not natural” nor the result of spring water, said heritage management expert May al-Ibrashy.

In a country already suffering from severe water scarcity, official figures show that more than a quarter of clean water produced never makes it to consumers.

Egyptians already consume slightly over half of what hydrologists consider the cut-off for water poverty at 1,000 cubic metres (35,300 cubic feet) per person annually, with the United Nations warning Egypt could “run out of water by 2025”.

In several heritage sites in Cairo’s historic Al-Khalifa neighbourhood which have not undergone renovation, Ibrashy’s team “tested the water, and the results are consistently that it’s drinking water mixed with sewage”.

That, she told AFP, “means there’s leakage” in the massive network of pipes that serves Greater Cairo’s 20 million inhabitants.

– Sunk cost –

The iconic mosques and mausoleums of historic Cairo — some submerged in up to a metre (yard) of water — lie lower than street level and are more permeable to groundwater than modern, insulated buildings.

These sites are also more susceptible to water damage because they are “near the Nile”, according to Mohamed Hassan Tawfik, a water resources management expert and PhD researcher at Wageningen University in the Netherlands.

But the problem extends well beyond the centuries-old domes of historic Cairo.

Nationwide, official figures show 26.5 percent of Egypt’s clean water in the 2021-22 fiscal year was lost — a conservative estimate, according to experts.

“The water company is producing that water, but… it goes into the ground,” Tawfik told AFP.

Globally, so-called non-revenue water drains hundreds of millions of cubic metres daily from faucets.

“You see these leakages happening in a system like ours that is itself very dilapidated and full of cracks,” Tawfik said, also pointing to “theft”, where people tamper with water meters or illegally reroute pipes.

The national Holding Company for Water and Wastewater does not disclose a breakdown of the loss by causes — leaks or illegal connections — and could not be reached for comment.

In major cities like Cairo, where 23.5 percent of clean water is lost, Ibrashy said many of the leaks occur in “the underground no-man’s land” between main pipes and buildings, where often neither authorities nor residents pay for maintenance.

“Because most of the network is very old” pipes cannot handle high pressure, which reduces efficiency and “causes leakages”, Tawfik explained.

The Suez Canal governorates of Port Said, Suez and Ismailia have the highest rates of water loss in the country, with over two thirds of clean water going down the drain.

– Swamp to garden –

Egypt simply cannot afford to be “paying to produce water that no one is using”, Tawfik said.

Hani Sewilam, Cairo’s irrigation and water resources minister, said this year individual consumers have access to around 550 cubic metres, a figure which officials expect to drop to 500 cubic metres by 2025.

With most leaks happening underground, water loss is an expensive problem to fix.

“Overhauling the system would cost billions,” according to Tawfik, as the country faces a punishing economic crisis and budget cuts.

Other possible solutions, including technologies that identify exact locations of leaks, require funding and political will from municipal authorities who have been largely reluctant to update practices, according to Ibrashy.

“The current approach in a lot of heritage sites is dewatering systems that take the water out to prevent water and salinity damage, and then feed it back into the sewage system,” she said.

“It’s a vicious cycle,” Ibrashy added, proposing instead “to take the water and use it”.

Across the street from Al-Ashraf Khalil, a canopy of trees hangs from a raised platform that houses Al-Khalifa Park, a 3,000-square-metre (0.74 acre) community garden and playground that was now “fed completely by groundwater” from the mausoleum and the nearby Fatima Khatun dome, Ibrashy said.

“Of course, you can’t use it to plant anything edible because there’s a risk of contamination,” she added, but it has provided a new green space in the densely populated neighbourhood of Cairo where such areas are scarce and shrinking.

The park’s irrigation system filters and reuses water that would have otherwise slowly risen to claim more of the centuries-old stone.

But as more water still seeps in across the street, such solutions are a drop in the ocean for the country of 105 million people, whose clean water needs continue to grow each year.