People in poorer countries are disproportionately suffering from air pollution spewed from the increasing scourge of fires in forests and fields around the world, according to new research published Wednesday.

Landscape fires include blazes in forests, shrub, grass, pastures and agricultural lands, whether planned or uncontrolled such as the wildfires that have ravaged countries including Algeria, Canada and Greece this year.

They generate smoke that can travel up to thousands of kilometres, creating public health risks, including increases in mortality and worsening of heart and lung-related illnesses.

Ambient air pollution caused some 4.5 million deaths in 2019, according to a study published in Lancet Planetary Health last year.

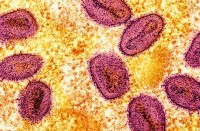

In a new study published in the journal Nature, researchers used data, machine learning and modelling to estimate global daily quantities of fine particles called PM2.5 and surface ozone concentrations emitted by landscape fires between 2000 and 2019.

The annual air pollution from landscape fires in low-income countries was around four times higher than in rich nations, they found, with central Africa, Southeast Asia, South America and Siberia experiencing the highest levels.

Increasing temperatures linked to human-caused climate change are increasing the risk of fire.

Shandy Li, an associate professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia who co-authored the study, said warming meant that the pollution “phenomena might be worse in the future”.

“Available evidence shows that fire smoke could increase health risks including mortality and morbidity, which means people should pay attention to reduce exposure to fire air pollution,” she told AFP.

Some 2.18 billion people a year on average were exposed to at least one day of “substantial” air pollution coming from landscape fire sources between 2010 and 2019, an increase of almost seven percent on the previous decade.

That includes daily average PM2.5 levels above 2021 WHO guidelines of 15 micrograms per cubic metre of air, where pollution from fire sources accounts for at least half of the total.

Africa had the highest average number of days of exposure to “substantial” fire-derived air pollution per person every year at 32.5, followed by South America at 23.1.

In contrast, Europeans were exposed to around one day of substantial pollution per year on average during the decade.

The five countries with the highest average annual number of days of exposure to substantial fire-sourced pollution per person were all African: Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Zambia, Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon.

– ‘Climate injustice’ –

In a separate study also published in Nature on Wednesday, scientists said wildfire smoke in the United States had eroded air quality progress achieved over decades.

Cities in rich countries also battle with poor air quality that breaches WHO guidelines, mostly due to pollution linked to transport, heating and industry.

Earlier this month, the UN World Meteorological Organization said climate change was driving more intense and frequent heatwaves and a subsequent “witch’s brew” of pollution.

Reducing extreme weather events by mitigating climate change would help limit the risk, Li said.

The researchers said their findings provided further evidence of “climate injustice” as those least responsible for human-induced climate change suffered the most from wildfires made more intense and frequent by it.

Changes to land management techniques, notably the burning of agricultural waste or blazes started deliberately to convert wildland for agricultural or commercial purposes, could also help reduce the extent of fires, they added.