Three researchers on Monday won a $700,000 prize for using artificial intelligence to read a 2,000-year-old scroll that was scorched in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

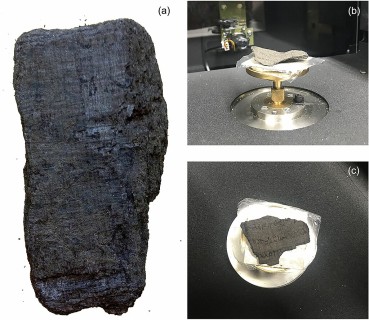

The Herculaneum papyri consist of about 800 rolled up Greek scrolls that were carbonized during the 79 CE volcanic eruption that buried the ancient Roman town of Pompeii, according to the organizers of the “Vesuvius Challenge.”

Resembling logs of hardened ash, the scrolls, which are kept at Institut de France in Paris and the National Library of Naples, have been extensively damaged and even crumbled when attempts have been made to roll them open.

As an alternative, the Vesuvius Challenge carried out high-resolution CT scans of four scrolls and offered one million dollars spread out among multiple prizes to spur research on them.

The trio who won the prize was composed of Youssef Nader, a PhD student in Berlin, Luke Farritor, a student and SpaceX intern from Nebraska, and Julian Schilliger, a Swiss robotics student.

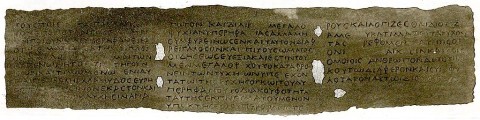

The group used AI to help distinguish ink from papyrus and work out the faint and almost unreadable Greek lettering through pattern recognition.

“Some of these texts could completely rewrite the history of key periods of the ancient world,” Robert Fowler, a classicist and the chair of the Herculaneum Society, told Bloomberg Businessweek magazine.

The challenge required researchers to decipher four passages of at least 140 characters, with at least 85 percent of characters recoverable.

Last year Farritor decoded the first word from one of the scrolls, which turned out to be the Greek word for “purple.”

Jointly, their efforts have now decrypted about five percent of the scroll, according to the organizers.

The scroll’s author was “probably Epicurean philosopher Philodemus,” writing “about music, food, and how to enjoy life’s pleasures,” wrote contest organizer Nat Friedman on X.

The scrolls were found in a villa thought to be previously owned by Julius Caesar’s patrician father-in-law, whose mostly unexcavated property held a library that could contain thousands more manuscripts.

The contest was the brainchild of Brent Seales, a computer scientist at the University of Kentucky, and Friedman, the founder of Github, a software and coding platform that was bought by Microsoft.

The recovery of never-seen ancient texts would be a huge breakthrough: according to data from the University of California, Irvine, only an estimated 3 to 5 percent of ancient Greek texts have survived.

“This is the start of a revolution in Herculaneum papyrology and in Greek philosophy in general. It is the only library to come to us from ancient Roman times,” Federica Nicolardi of the University of Naples Federico II told The Guardian newspaper.

In the closing section, the author of the scroll “throws shade at unnamed ideological adversaries — perhaps the stoics? — who ‘have nothing to say about pleasure, either in general or in particular,'” Friedman said.

The next phase of the competition will attempt to leverage the research to unlock 85 percent of the scroll, he added.