Mindoro – Our boat fights the fury of Amihan, the northeast monsoon. I’m just fighting to keep my dinner down.

Mindoro – Our boat fights the fury of Amihan, the northeast monsoon. I’m just fighting to keep my dinner down.

It’s night and we’re on the Princess Camile, a tuna vessel going head-to-head with angry six-foot waves. I gaze out at the darkness. I have no idea where we are – but a little gadget attached to our boat mast does.

To track the routes of fishing boats in the Mindoro Strait, WWF and NAVAMA have outfitted 13 vessels with satellite trackers, the same kind used for commercial cargo.

“These use cellular or satellite networks to plot GPS coordinates and visually depict vessel routes. This is crucial for safety and to ensure that boats fish only in proper zones,” explains NAVAMA chief engineer Simon Struck. “The matchbox-sized devices are weatherproof, economical and simple to use.”

With local fishers, government leaders, plus the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR), WWF and NAVAMA are promoting fisheries transparency and safety at sea through the Smart Track Project.

Promoting Transparent, Sustainable Fishing

Fisheries transparency – where and how fish are caught – is a global issue. Too often are fish gathered through illegal means or in protected areas. Many catches remain unreported.

In December of 2006, the M/V Hoi Wan, a Chinese fishing vessel, was caught poaching off the Tubbataha Reefs in Palawan. Amongst its catch were 359 legally-protected Napoleon Wrasse, which can be illegally sold for P6000 per kilogramme.

The European Union estimates that about 26 million tonnes of seafood – 15% of global yields – are caught via Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated (IUU) fishing. The Philippines was issued a yellow card in June 2014 for failing to curb IUU fishing. The rating warned the country that unless it addressed IUU fishing, its seafood products would be banned in Europe.

Fortunately, the yellow card rating was lifted in April 2015, after the government replaced its ancient fisheries code with Republic Act 10654 while vigorously promoting sustainable fishing.

Pilot-Testing the Trackers

Back on the Princess Camile, one of our fishers finally gets a bite. He jerks up and furiously pumps a circular handline reel. We watch in silent anticipation and expect what must surely be the largest tuna ever pulled up from Mindoro’s depths. Something swims and crashes to the surface …

He shrugs and shakes his head. “Only a tuki. Snake mackerel.” Though we didn’t score any tuna, we smile as our boat does a 180 turn. Our sea legs will be glad to be on terra firma.

“Fishers aboard satellite-equipped boats can proudly show the world that they only fish in proper zones,” shouts team leader Joann Binondo above the whistle of the wind. Binondo heads WWF’s Partnership Programme Towards Sustainable Tuna (PPTST). Since 2011, they’ve been working to enhance yellowfin tuna management practices for 5800 fishers in 112 tuna fishing villages in Bicol and Mindoro.

Funded by Bell Seafood, Coop, Marks & Spencer, New England Seafood, Seafresh, Waitrose and the German Investment and Development Corporation, PPTST works with Bicol and Mindoro LGUs, BFAR, WWF International, WWF-Germany, plus European seafood companies and their local suppliers. It has spearheaded the registration and licensing of tuna fishers, vessels and gear to minimize bycatch and illegal fishing.

WWF believes in technology and innovation as conservation aids. “We hope these satellite trackers will become mandatory equipment for all commercial fishing vessels,” says Binondo. “Just knowing where our fish comes from is a big step in curbing IUU fishing.”

* * *

It’s nearly midnight when we glimpse the faint lights of Mamburao. Illuminated by moonlight are hundreds of moored fishing boats. Mamburao’s fleet is a thousand strong, with a single boat landing 45 yellowfin tuna in just five days. That’s a whole lot of fish, which is why WWF is helping locals manage these stocks.

Quietly, we drop anchor and glide to shore. “Wonder where we caught that snake mackerel,” asks Binondo. Smiling, I glance at the boat’s satellite tracker. “I’m not sure. But we’ll know really soon.”

Fisherman Emelito Macaraig displays one of 13 satellite trackers installed by NAVAMA and WWF in Mamburao, Occidental Mindoro. The devices use satellite or cellular networks to chart vessel routes, which can be viewed through the SeeOcean Explorer platform on the web. (Gregg Yan / WWF)

All-weather satellite tracker plots coordinates every 15 minutes, 200 meters or each time the vessel alters its course by 30 degrees. It is mounted below a boat’s mast and draws power from batteries – though it can be rigged to an engine or a solar-powered system. (Gregg Yan / WWF)

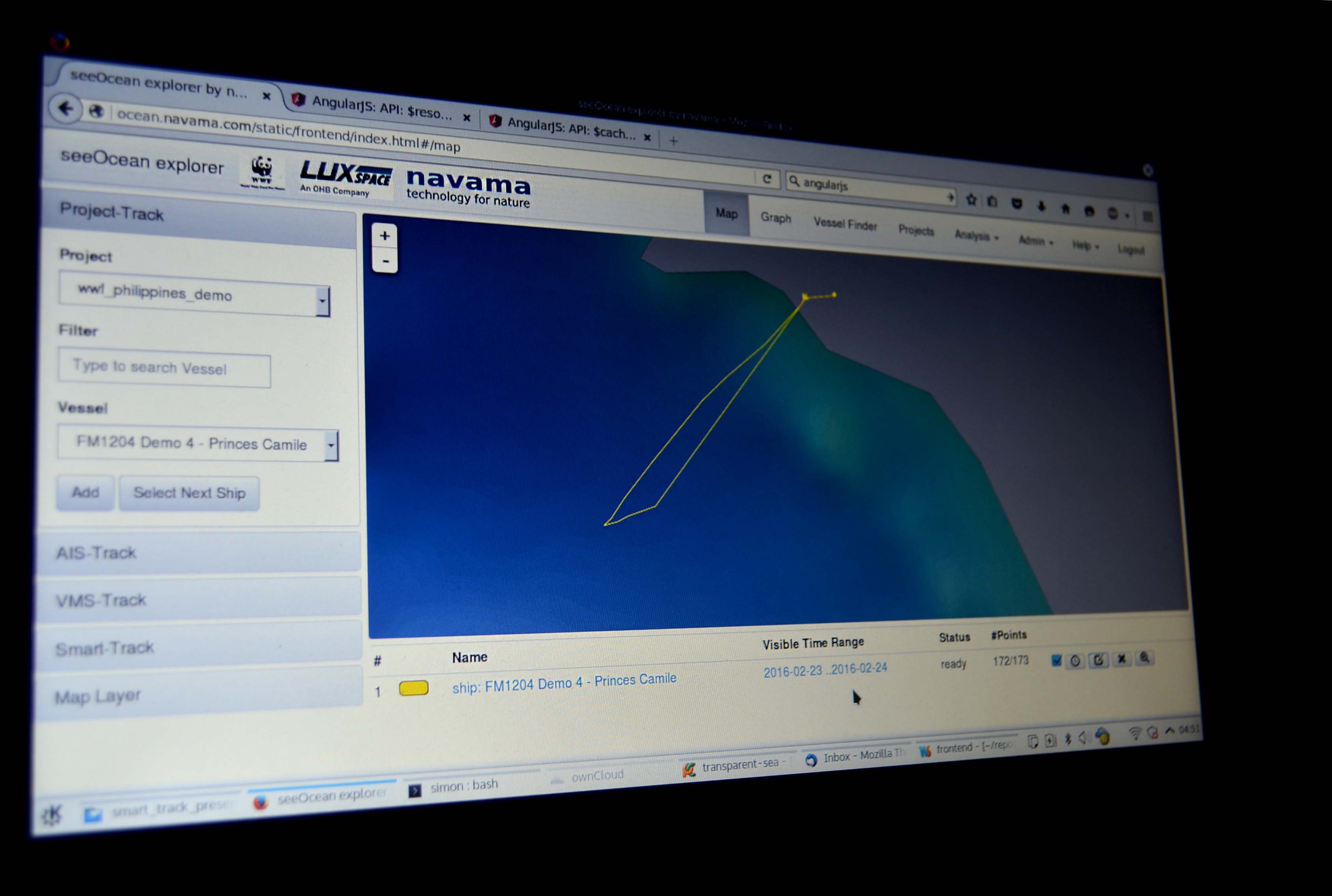

Route of the Princess Camile, our fishing boat. We sailed about 11 kilometers southwest of Mamburao before heading back. (NAVAMA / WWF)

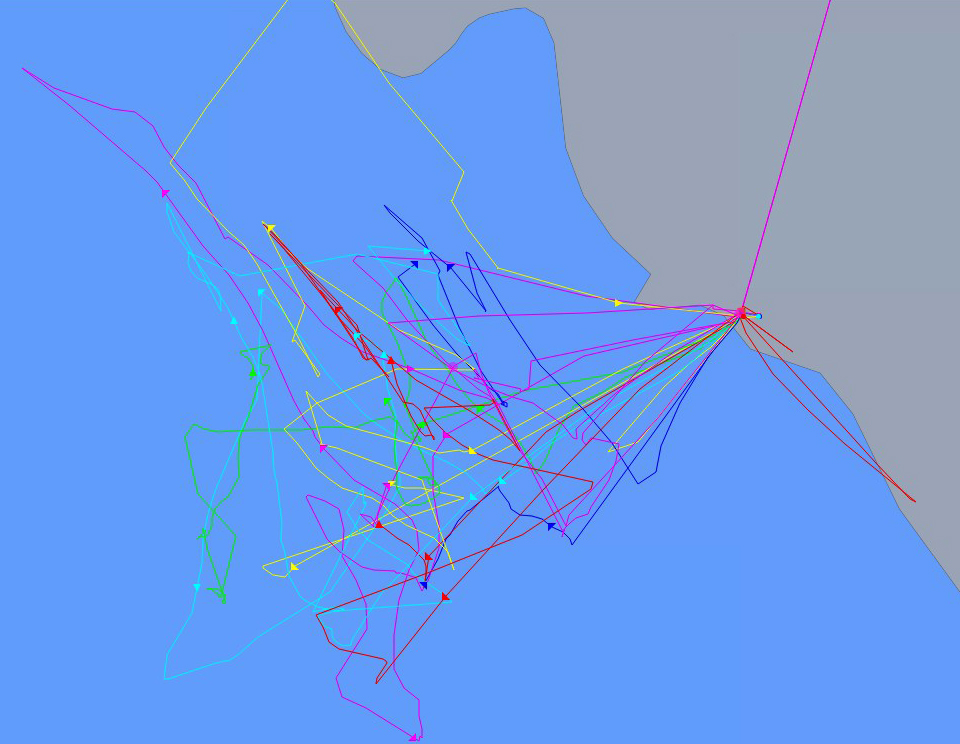

Precisely-plotted routes of all 13 vessels with satellite trackers as seen on the SeeOcean Explorer platform. None approached Apo Reef, a protected area southwest of Mamburao. (NAVAMA / WWF)

Circular tuna handline reel with a lead sinker and hook. Handline reels minimize the global problem of bycatch – the unintended capture of non-targeted species which wastes up to 40% of global yields annually – by catching just one large fish at a time. (Gregg Yan / WWF)

The catch o’ the day! A live yellowfin is hauled up from the depths of the Mindoro Strait. “The best time to hunt tuna is on a moonless night,” shares boat captain Johnson Peralta. “The darkness makes it easier for our boat’s lights to attract fish.” (Gregg Yan / WWF)

Tuna are top Philippine exports. Five species form the majority of commercial exports. The most valuable is the yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares), which comprises about 40% of all yields. However, unsustainable fishing has caused yellowfin tuna catches to drop by 75% in just 20 years. Fishers which used to catch them within 15 kilometers from shore now travel up to 100 kilometers to find their quarry. Shown is a fisher with a 42 kilogramme yellowfin in Mamburao, Occidental Mindoro. (Gregg Yan / WWF)

(from Gregg Yan, World Wide Fund)