by Sara HUSSEIN

Agence France-Presse

TOKYO, Japan (AFP) — Scientists had nicknamed it “The Thing” — a mysterious football-sized fossil discovered in Antarctica that sat in a Chilean museum awaiting someone who could work out just what it was.

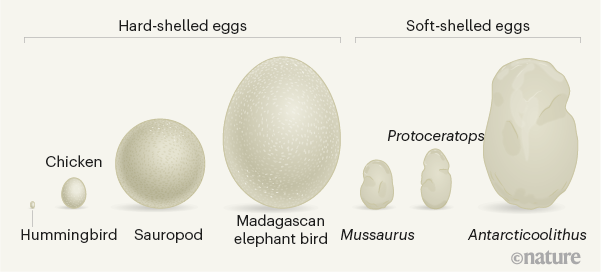

Now, analysis has revealed the mystery fossil to be a soft-shelled egg, the largest ever found, laid some 68 million years ago, possibly by a type of extinct sea snake or lizard.

The revelation ends nearly a decade of speculation and could change thinking about the lives of marine creatures in this era, said Lucas Legendre, lead author of a paper detailing the findings, published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

“It is very rare to find fossil soft-shelled eggs that are that well-preserved,” Legendre, a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Texas at Austin, told AFP.

“This new egg is by far the largest soft-shelled egg ever discovered. We did not know that these eggs could reach such an enormous size, and since we hypothesise it was laid by a giant marine reptile, it might also be a unique glimpse into the reproductive strategy of these animals,” he said.

The fossil was discovered in 2011 by a group of Chilean scientists working in Antarctica. It looks a bit like a crumpled baked potato but measures a whopping 11 by seven inches — 28 by 18 centimetres.

For years, visiting scientists examined the fossil in vain, until in 2018 a palaeontologist suggested it might be an egg.

A mammoth find

It wasn’t the most obvious hypothesis given its size and appearance, and there was no skeleton inside to confirm it.

Analysis of sections of the fossil revealed “a layered structure similar to a soft membrane, and a much thinner hard outer layer, suggesting it was soft-shelled,” Legendre said.

Chemical analyses showed “the eggshell is distinct from the sediment around it, and was originally a living tissue.”

But that left other mysteries to unravel, including what animal laid such an enormous egg — only one bigger has been found, produced by the now-extinct elephant bird from Madagascar.

The team believe this egg wasn’t from a dinosaur — the types living in Antarctica at the time were mostly too small to have produced such a mammoth egg, and the ones large enough laid spherical, rather than oval-shaped, ones.

Instead they believe it came from a kind of reptile, possibly a group known as Mosasaurs, which were common in the region.

Soft-shelled dinosaur eggs

The paper was published in Nature along a separate study that argues that it wasn’t only ancient reptiles that laid soft-shell eggs — dinosaurs did too.

For years, experts believed dinosaurs only laid hard-shelled eggs, which are all that had been found.

But Mark Norell, curator of palaeontology at the American Museum of Natural History, said the discovery of a group of fossilised embryonic Protoceratops dinosaurs in Mongolia made him revisit the assumption.

“Why do we only find dinosaur eggs relatively late in the Mesozoic and why only in a couple groups of dinosaurs,” he said he asked himself.

The answer, he theorised, was that early dinosaurs laid soft-shell eggs that were destroyed and not fossilised.

To test the theory, Norell and a team analysed the material around some of the Protoceratops skeletons in the Mongolia fossil and another fossil of two apparently newborn Mussaurus.

They found chemical signatures showing the dinosaurs would have been surrounded by soft, leathery eggshells.

“The first dinosaur egg was soft-shelled,” Norell and his team conclude in the paper.

Norell’s findings may have implications for the fossil once named “The Thing” — which is now known as Antarcticoolithus, according to a review of the studies published in Nature.

They “could implicate some form of dinosaur as the proud parent,” wrote Johan Lindgren of Lund University and Benjamin Kear of Uppsala University.

“Let us hope that future discoveries of similarly spectacular fossil eggs with intact embryos will solve this thought-provoking enigma.”

© Agence France-Presse