Colombia’s President Juan Manuel Santos dedicated his Nobel Peace Prize Friday to the victims of his country’s civil war, which he has worked to end through a contested peace accord with communist rebels / AFP PHOTO / GUILLERMO LEGARIA

OSLO, Norway (AFP) – by Hazel WARD

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos won the Nobel Peace Prize Friday for his “resolute” efforts to end more than five decades of war in his country, despite voters’ shock rejection of a historic peace deal.

The award was unexpected after voters rejected the terms of a landmark accord Santos clinched last month with FARC leader Rodrigo Londono, alias Timoleon “Timochenko” Jimenez and some observers expressed surprise the rebel chief did not jointly receive the prize.

The Norwegian Nobel committee rewarded Santos for his “resolute efforts to bring the country’s more than 50-year-long civil war to an end,” announced chairwoman Kaci Kullmann Five.

The deal, signed on September 26 after nearly four years of talks, was supposed to be ratified following an October 2 referendum but voters shot down the agreement, leaving the country teetering between war and peace.

The result caught most Nobel watchers off-guard, with most experts predicting the referendum would scupper Colombia’s chances.

But the committee said the aim was to encourage peace efforts in the war-torn country, which are now in “real danger” of collapse.

“We hope that it will encourage all good initiatives and all the parties who could make a difference in the peace process and give Colombia — finally — a peace after decades of war,” Kullman Five said.

For his part, Santos said he thought peace was “very, very close” as he accepted the award on behalf of the Colombian people “who have suffered so much.”

In an interview with the Nobel Foundation, Santos added that the award was a “great stimulus” in the quest for peace.

“The message is that we have to persevere and reach the end of this war. We are very, very close, we just need to push a bit further,” Santos was quoted as saying.

‘Countless victims’

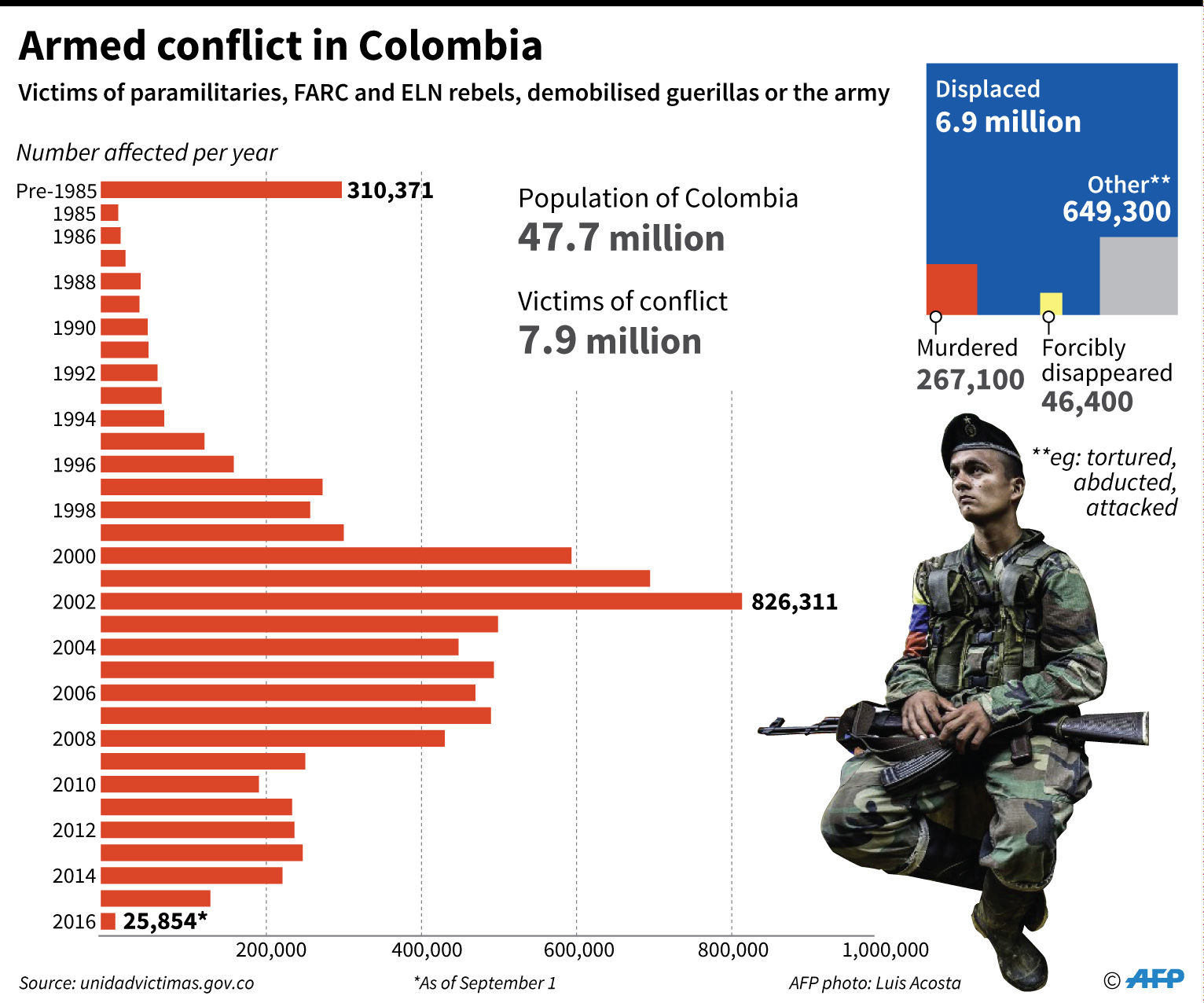

The Colombia conflict has claimed more than 260,000 lives and left 45,000 missing over five decades, drawing in several leftist guerrilla groups, right-wing paramilitaries and drug gangs.

Under the terms of the deal, FARC, the oldest and largest rebel group, was to relaunch as a political party.

The rejection of the terms of the deal followed a successful campaign by rightwing hardliners angered by the offer of impunity for the Marxist rebels.

Paying tribute to the Colombian people and the “countless victims” of the war, the Nobel committee urged both sides to “continue to respect the ceasefire” that expires at the end of the month.

“There is a real danger that the peace process will come to a halt and that civil war will flare up again,” Kullmann Five said.

Santos, who has staked his legacy on making peace, has warned that Colombia is now in a “very dangerous limbo.”

FARC leaders have vowed they are committed to making peace, but it is unclear whether they will be able to sell a new deal to the rank and file.

Fourth Nobel

Nobel watchers had initially tipped Santos and Timochenko as likely winners of the prestigious prize but quickly revised their predictions after the referendum, saying such an award would be perceived as flying in the face of the will of the Colombian people.

Asked why the prize had not been jointly awarded to the FARC leader, Kullman Five declined to answer, saying: “We will never comment on other candidates and other possibilities.”

The Nobel committee has however in the past honoured former enemies for peace processes at fragile stages, including those in Northern Ireland and the Middle East.

Ingrid Betancourt, who spent six years in the jungle after being abducted by FARC while campaigning in presidential elections in 2002, said FARC should have shared the prize.

The Norwegian Nobel committee has in the past awarded the prize to those involved in peace efforts which had yet to bear fruit, with the express aim of encouraging them.

The peace prize is the fourth Nobel to be announced this week.

On Monday, Yoshinori Ohsumi of Japan won the medicine prize for his pioneering work on autophagy, a process whereby cells “eat themselves” which can result in Parkinson’s and diabetes when disrupted.

And on Tuesday, the physics prize went to British scientists David Thouless, Duncan Haldane and Michael Kosterlitz for their work on “topology”, a highly specialised mathematics field studying unusual phases or states of matter.

Wednesday’s chemistry prize went to Jean-Pierre Sauvage of France, Fraser Stoddart of Britain and Bernard Feringa of the Netherlands for developing the world’s smallest machines that may one day act as artificial muscles to power tiny robots or even prosthetic limbs.

The economics prize will be announced Monday, and the 2016 Nobel season will end on Thursday with the literature prize, which is being presented a week later than normal.

The peace prize is a gold medal, a diploma and a cheque for eight million Swedish kronor (around $932,000 or 831,000 euros) which will be presented at a ceremony in Oslo on December 10, the anniversary of the 1896 death of prize creator Alfred Nobel, a Swedish philanthropist and scientist.