PHL history professor analyzes the similarities between the two pandemics set a century apart, and what lessons could be learned from the 1918-1919 flu pandemic

(Eagle News) – A hundred years ago, from 1918 to 1919, a virus pandemic infected 500 million worldwide – a third of the world’s population at that time – killing as many as 50 million people, according to conservative estimates.

In the Philippines, the so-called “Spanish flu” pandemic killed 90,000 people in 1918 alone amid a post-World War I era that had decimated millions across the globe.

And the virus, swept across countries, in three waves killing more people in two years (from 1918-1919) than World War I which had a death toll of 40 million from 1914 to 1918.

A Filipino historian, Prof. Francis Gealogo, wrote about this deadly flu pandemic in the context of the Philippine situation in an academic paper, “The Philippines in the World of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919” which appeared in the “Philippine Studies” journal published in 2009 by the Ateneo de Manila University.

Gealogo sees many similarities between the 1918-1919 pandemic and the current coronavirus pandemic that as of this writing has infected more than six million people across the world, killing more than 370,000 people.

And the history professor says that policymakers should learn the lessons of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic.

-A “racialized pandemic”-

First, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 like the COVID-19 pandemic was “initially identified with a particular nationality.”

“Unang, una yung similarity na initially they thought it can be identified as a disease associated with a particular nationality or group of people,” Gealogo said in an interview with Eagle News online.

He said that the flu pandemic happened towards the end of World War 1 where there was a lot of censorship. Spain being a neutral country, reported how there were many deaths due to a still unexplainable disease of unknown origin at that time, although this disease was also happening in other parts of the world but was not reported extensively.

“In Spain, nauna itong nai-report kaya sabi nila, ah, it is a Spanish disease (It was in Spain that it was first reported, so they thought it was a Spanish disease)” Gealogo explained.

When it spread in France, it was reported as German flu. And in England, it was known as “Chungking fever” because there were many Chinese who were getting sick at that time.

“Parang ngayon din, na-racialize ang disease, sa ibang bansa mayroong perception , even in the Philippines na lahat ng mga Chinese ay carriers,” Gealogo as he noted “racist backlash” in the first few weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the infection was associated with the Chinese or Asians in general.

-Importance of immediately reporting an outbreak –

Secondly, the relevance of reporting was very important, he said.

Influenza cases, at the onset of the flu pandemic in 1918, were not initially considred a “reportable disease” then. These were not initially recorded or reported.

“So it’s very important to recognize the existence of an outbreak right at the very moment and report it correctly, record it correctly, so that authorities can take the necessary measures towards the control of the disease,” Gealogo said.

“Kung walang free flow of information ma-co-compromise yung idea of control of the disease. So that’s the second similarity.”

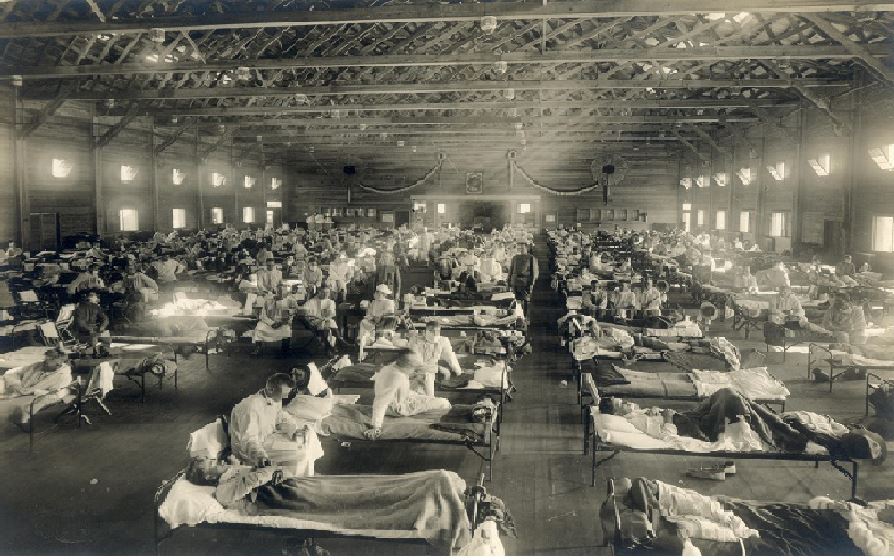

“The third similarity – overwhelming yung pandemic nung 1918. Ibig sabihin, those in the medical field were not able to cope with the outbreak,” he said.

Gealogo said that at present, there is an Inter-Agency Task Force on Emerging Infectious Diseases (IATF-EID) which could have anticipated this, given the extensive historical experience that we have.

“So may anticipation, may SARS na niyan, may Ebola na yan…Authorities should have prepared. Maaring hindi COVID, pero dapat may in place na established protocols kung anong gagawin,” he said.

In 1918, they simply didn’t know this, he said, and the health system then was overwhelmed. At that time also, World War 1 had also taken its toll on the health service personnel. And the lack of knowledge about the pandemic then, also affected the health system so that many of them were infected and had died.

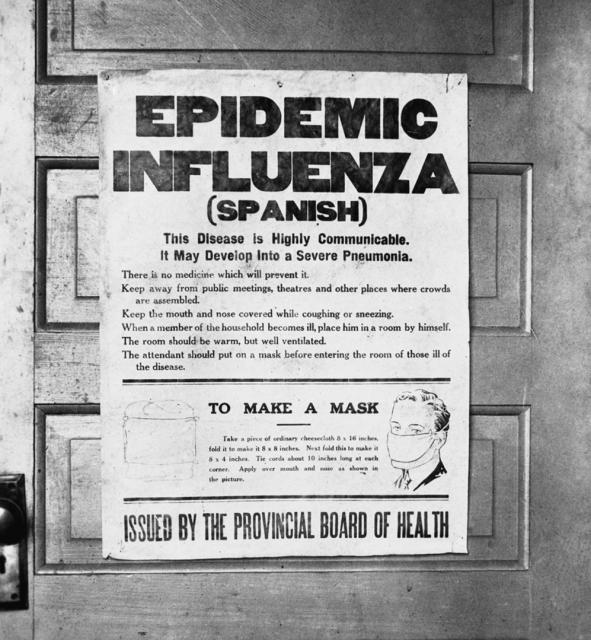

It was during that time that the use of face masks and isolation protocols were first used to prevent the spread of the infection.

In 1918, they initially even thought that the disease was caused by a bacteria and not a virus as we know now.

“Mahalaga ito, Kasi ngayon, mas scientific na ang kaalaman natin. Mas extensive na ang historical experiences. We should have learned from that. Kaya lang hindi tayo natuto and na-overhwhelm ang ating health institutions,” he said.

-Infections among health care personnel-

In 1919, the very first Filipino director of the Philippine Bureau of Health, Dr. Vicente de Jesus — the father of Filipino poet Jose Corazon de Jesus or Joseng Batute — also got infected with influenza.

So in the middle of the outbreak, Dr. De Jesus was indisposed and wasn’t able to direct efforts in the middle of the pandemic, Gealogo said.

As in the flu pandemic of 1918-1919, the present-day COVID-19 pandemic had also infected a lot of health care personnel, he said.

Similarly, the Philippine health bureaucracy then was understaffed, compromising the efforts to address the pandemic.

“Kagaya ngayon, even before the outbreak, wala namang World War, pero we had a significant budgetary cut, significant cuts in the number of items for personnel, medical professionals and the like. Significant yun, kasi yung kakayahan ng institution to make a professional intervention was compromised,” he said.

In 1918, because of resignations in the public health system, and reassignments made in the war front before this, and the perennial lack of budget, the Philippine heath bureaucracy wasn’t able to cope with the outbreak.

-Not all virus fatalities reported-

Almost 90,000 deaths were recorded then from the virus in 1918 alone in the country, but Gealogo suspects that these were just conservative estimates as not all deaths related to the flu pandemic had been recorded, particularly in the Cordillera and in Mindanao.

This number of deaths then were very significant as the population then was only around 20 million, compared to the present around 100 million population in the country, Gealogo noted.

-Deaths in 3 waves of the pandemic-

Another similarity of the virus pandemic in 1918-1919 and today’s coronavirus pandemic was the occurrence of the mass infections and deaths in waves.

In fact, a hundred years ago, the flu pandemic occurred in three waves, the first wave being the less number of infections in June and July of 1918, followed by a dip of infections in August and September when authorities thought that the worst of the pandemic was over following limitations in public gatherings.

In October 1918, the infections began to pick up. Historical records show that the flu pandemic of 1918 killed hundreds in June and July. Starting October to December 1918, the deaths reported were in the thousands.

In October 1918, the deaths reported were 2,237 in the Philippines. By November, the deaths reported due to the virus jumped to 48,523.

In December 1918, the fatalities were 35,204 based on Philippine census reports at that time.

-Second wave that had the highest deaths came after easing quarantine restrictions-

“Parang nakampante sila by October (1918), akala nila wala na. Pero yung second wave, November, December, yun ang talagang pinakamaraming namatay,” Gealogo pointed out.

He noted that after the first wave of the pandemic, authorities had relaxed restrictions and opened schools and other public places, which was the reason for the higher second wave of infections.

“So they limited public gatherings in the first wave. Pero nag-relax, binuksan pa nila mga eskuwelahan by November. Even in UP (University of the Philippines), may mga teachers namatay, may mga students na namatay,” he noted.

That was the period of enrollment for the second semester then. Because of the second wave of the outbreak, they had to suspend the entire semester, he said.

There was even a third wave in 1919, sometime in March and April, but the infections and deaths were less than the second wave.

This was probably because many had developed the so-called “herd immunity” at that time, because of antibodies developed from the first instances of the pandemic.

-A third wave of the pandemic-

“Nagka-third wave ng 1919 March, although not as dramatic as the second wave. Marami pa rin ang namatay noong March and April of 1919, pero di pa rin nakapag-develop ng vaccine,” Gealogo said.

He said that the flu vaccine was developed years later, some 20 years later.

In fact, the vaccine for the flu pandemic is what is known as the present-day flu shots.

-Vaccine for flu developed 20 years later-

Historical records also showed that although there were attempts to develop a vaccine during the 1918-1919 pandemic, the functional versions of flu vaccines in the US began in the 1940s, according to an article which appeared in “Eureka: Voices and Stories from the Front Pages of Science” in 2018.

It said that in the US, the functional version of the flu vaccines began in the 1940s, which was 20 years later after the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

“The first approved version of the vaccine was administered to soldiers in 1945, during World War II. Civilians were able to get vaccinated the following year,” said the article, “The Great Pandemic 100 years later” written by Mary Parker that appeared in the Eureka website in October 2018.

-1918 pandemic killed mostly the young and healthy-

Another characteristic of the 1918-1919 flu pandemic was that most of the deaths were the young supposedly healthy bodied individuals, and not the very young and the very old as what usually happens in most pandemics.

This happened mostly in the second wave of the pandemic.

It appears that some of the elderly sector had developed a natural immunity from previous flu infections, noted Geologo.

“What’s peculiar in 1918 was that they noticed that a number of the victims of the influenza outbreak were actually young adults, hindi pa yung elderly, but the supposedly able bodied, healthy aged individuals,” he said.

Gealogo said that there was a suspicion that an earlier mild outbreak in the 1890s left the elderly who survived that disease with a natural immunity.

“So those elderly who survived that outbreak in the 1890s, were already very old in 1918, pero may immunity sila (but they had immunity) .”

(Eagle News Service)