(REUTERS) Elderly Japanese, among the world’s richest retirees, are flocking to inheritance advisers, tackling historical taboos on discussing death and providing a rare avenue of growth for the country’s brokerages and banks.

Trillions of dollars parked in savings accounts are set to be released in the coming years as Japan’s death rate climbs and new, more onerous inheritance tax rules kick in.

The shift is attracting investment from companies such as Nomura Holdings, Daiwa Securities Group and Mizuho Financial Group which are ramping up offerings of inheritance-related services and products, hoping to lock in a new generation of customers.

“Until now, Nomura has dealt with its customers individually. When they pass away, that connection ends. We want their children to become customers,” said Naoshi Sakai, who oversees trusts at Nomura Securities, a subsidiary of Nomura Holdings.

“Business chances for domestic sales will get smaller as the population shrinks, and we have to avoid that. Inheritance is one business that will certainly grow in the next 20 years.”

Over $470 billion – nearly Norway’s GDP – in financial assets is passed on annually in Japan, Nomura Institute of Capital Markets Research estimates. That figure, which includes property, is set to grow to $660 billion a year by 2030. Cumulatively, more than $4.7 trillion, equivalent to Japan’s GDP, will be passed down by 2030.

As families plan to deal with this flood of funds, discussion of mortality is becoming more common. Interest in “shukatsu” – literally preparing for the end – has boosted death-related businesses, from try-before-you-die coffins to funeral planning.

“My sons are starting to give their opinion on inheritance, and I’m interested,” 84-year-old Susumu Yokoyama told Reuters after a recent Nomura seminar on estate planning in Tokyo. “I’m thinking about what to do.”

With high stakes comes fierce competition.

Trust banks such as Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank Ltd, traditionally the main providers of inheritance services, are facing a push from banks such as Mizuho, which are seeking to bolster their asset management businesses as negative interest rates sap returns and demand for loans remains tepid.

Providers of inheritance trusts are licenced by Japan’s financial regulator and consumers have on the whole escaped the widespread misselling of financial products that saw Western financial institutions fined billions of dollars by regulators.

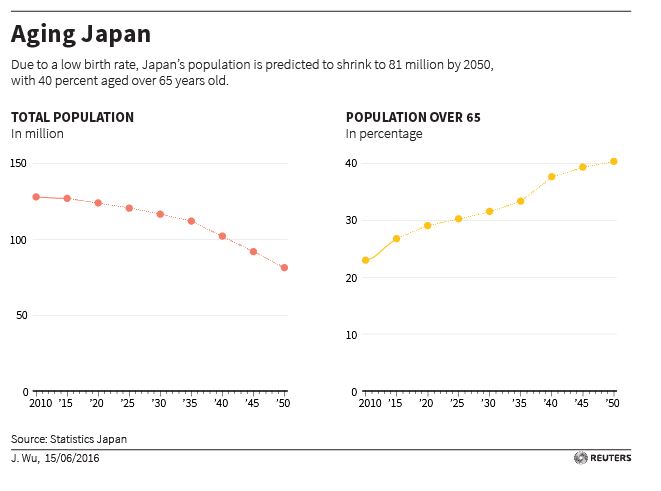

Due to a rock-bottom birth rate, Japan’s population is shrinking and aging fast. The government predicts the population will fall to barely 80 million by 2050 from 127 million last year. By then 40 percent of people will be over 65, compared to 27 percent last year. They’re also expiring faster than ever: the national death rate spiked to 10.4 deaths per 1,000 people last year from 9.5 in 2010.

But they are wealthy. Over 60-year-olds own more than half of the country’s $14 trillion in personal financial assets, according to the Bank of Japan.

The Japanese government, however, wants a bigger slice.

Japan already has among the highest inheritance tax in the world with a top rate of 55 percent, and changes introduced last year lowered the threshold for paying the tax to $280,000 from $471,000.

In the United States, the threshold is $5.5 million with a top rate of 40 percent, while numerous countries including China and 15 OECD nations have no inheritance tax.

At a recent seminar in Yokosuka, a port city southwest of Tokyo, retirees sipped green tea and listened as a speaker laid out options for inheritance, applauding as the talk ended.

“I ought to think of how I can move money a little at a time to my wife’s name, or within my family,” said Hideo Tsujii, a spry 83-year-old. “I want them to estimate how much I have in assets, then I can decide what to do.”

Tsujii, a great-grandfather who’s had mutual funds and savings with Daiwa for 20 years, is the kind of customer financial institutions are seeking to attract, even if he doesn’t buy any new products.

“The service itself doesn’t make money for Daiwa, but instead allows money to remain within the company,” said Kazuhiro Hosoda, managing director at Daiwa’s wealth management division. “Profits will likely expand in the future.”

But even as the sector grows, death remains the elephant in the room for those selling the products. Marketing materials use phrases such as “preparing for the future” or “memories for your family,” and sellers tread carefully when meeting customers.

“We discuss inheritance not in terms of “what will you do when you die?” but rather in terms of how you can leave assets to your family,” said Takayuki Konno, a marketing manager at Mizuho responsible for inheritance-related services.

“It’s a practical problem that people want to solve.”