by Annie THOMAS and Lucien KAHOZI

Agence France-Presse

MANONO, DR Congo (AFP) – Near the rusting carcass of a smelter, barefoot men and women scratch at the ground in the quest for cassiterite — the tin oxide ore that generations ago gave the town of Manono a brief taste of the good life.

The diggers carry the sandy earth to the Lukushi River where women wash the grit in metal bowls, hoping to find some black nuggets from which to make a living.

Standing in the water from morning to evening, washing the spoil and looking for ore brings in between 15,000 and 18,000 Congolese francs ($7.50 to $9.00 / 6.70 to eight euros) per day.

“There is nothing else in Manono,” said Marcelline Banza, a 28-year-old mother of three. “Life is very difficult.”

Manono, a town in Tanganyika province in southeast DR Congo, is almost a textbook case of a mining town that went from boom to bust.

“Most of the people live below the poverty line and prefer to dig (for cassiterite) rather than work the fields,” said Patrice Sangwa, the district’s head doctor.

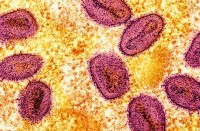

This isolated corner of the vast country is battling malnutrition, cholera and even a measles epidemic, which has killed dozens of children since December.

But hopes are rising that the impoverished town could be magically transformed.

The big news is that a large deposit of lithium — the metal used to make rechargeable batteries in phones and electric cars — has been found nearby.

Quality ore

After several years’ exploration, Australian company AVZ Minerals, which owns a majority stake in a joint venture with Congolese firm La Cominiere, says it has discovered around 400 million tonnes of ore with a lithium concentration of 1.6 percent.

The find represents lithium reserves of some six million tonnes — more than enough to compete with leading producers such as Australia, Chile, Argentina and China.

“It probably stands at the largest undeveloped resource in the world,” said AVZ’s chief executive, Nigel Ferguson, describing the find as “very unique.”

“The quality is very good… very pure all the way through,” he said.

In large sheds, the company stores cores drilled out of the rock at a depth of nearly 400 meters (1,300 feet), below the layers of soil, laterite and shale.

The samples are sent for analysis to Perth in Australia.

Glory days

Manono grew from the beginning of the 20th century, when Belgian settlers exploited a promising cassiterite deposit.

The mines, along with quarries, foundries, dams, housing and the railway, brought prosperity.

But little by little, after the turbulent years and shoddy management that followed independence in 1960, mining equipment deteriorated and Manono gradually became dormant.

Decline was abetted by falling prices for tin, although the coup de grace came from the war that led to the seizure of power in 1997 by Laurent-Desire Kabila, supported by Rwandan soldiers.

“We all fled. The foundry was destroyed, the houses looted, the European district devastated, that of the African executives too,” recalled Paul Kissoula, a respected elder aged 70 who goes by the nickname of “Papa Paul.”

A quarter of a century on, vegetation has grown over the ruins and slag heaps are covered with trees, while two steam locomotives, a crane and wagons are rusting by a roadside.

“There hasn’t been anything for years,” said “Papa Paul.”

He was hired in 1974 by Congo Etain (Congo Tin) — a public company that became Zairetain after the country changed its name to Zaire under the dictatorship of Marshal Mobutu Sese Seko, then La Cominiere (Congolese mining company).

‘Waiting for the licence’

AVZ is hoping for an operating licence after submitting a feasibility study for the site.

The company says it plans to invest $600 million to build a lithium processing plant with a capacity of 700,000 tonnes per year, and rehabilitate an old hydroelectric plant to provide power.

If all goes well, production could start in 2023, and hundreds of people could be employed, according to its scheme.

“People are suffering… AVZ will help us,” said territorial administrator Pierre Mukamba Kaseya who, like everyone else, is “waiting for the licence.”

“The project specifications also provide for work on roads, schools, hospitals,” said Baccam Banza Cazadi, head of a secondary school.

“We want them to be able to succeed, for the province and for the country,” he said. “There is hope.”

© Agence France-Presse