(Reuters)

A woman who died of Ebola this week in Sierra Leone potentially exposed dozens of other people to the disease, according to an aid agency report on Friday, raising the risk of more cases just as the deadliest outbreak on record appeared to be ending.

Just a day earlier, the World Health Organization (WHO) had declared that “all known chains of transmission have been stopped in West Africa” after Liberia joined Sierra Leone and Guinea in going six weeks with no reported new cases. The three countries had borne the brunt of a two-year epidemic that killed more than 11,300 people.

The WHO warned of the potential for more flare-ups, as survivors can carry the virus for months. But the new case in Sierra Leone is especially disquieting because authorities failed to follow basic health protocols, according to the report seen by Reuters.

Compiled by a humanitarian agency that asked not to be named, the document said the victim, Mariatu Jalloh, had come into contact with at least 27 people, including 22 in the house where she died and five who were involved in washing her corpse. But its account suggested others could also be at risk.

Jalloh, 22, began showing symptoms at the beginning of the year, though the exact date is unknown, the report states. A student in Port Loko, the largest town in Sierra Leone’s Northern Province, she traveled to Bamoi Luma near the border with Guinea in late December.

Sierra Leone’s northern border area, a maze of waterways, was one of the country’s last Ebola hot spots before it was declared Ebola-free on Nov. 7, and contact tracing was sometimes bedeviled by access problems.

By the time she traveled back to her parents’ home in Tonkolili district, east of the capital Freetown, using three different taxis, Jalloh had diarrhea and was vomiting, the report said.

She sought treatment at the local Magburaka Government Hospital on Jan. 8 where a health worker, who did not wear protective clothing, took a blood sample. It was not immediately clear whether the sample was tested for Ebola.

She was treated as an outpatient and returned home, where she died on Jan. 12. Health workers took a swab test of Jalloh’s body following her death, which tested positive for Ebola.

“The sample was tested for the first time on Thursday morning – around the same time as the WHO declared the Ebola outbreak over”, said Tim Brooks of Public Health England, the British agency that tested the sample at its lab in Sierra Leone.

PUBLIC ANGER

The missed diagnosis has led to anger in some quarters. Dozens of young people gathered outside the hospital on Friday in a noisy demonstration, some holding placards accusing the health department of negligence.

“We are demonstrating because we want the authorities to explain to us why the woman was discharged and allowed to go home, where she died, and her corpse was given to her family to bury. We are now concerned that some family members may have been infected,” said local youth leader Mahmud Tarawally.

Asked about apparent errors in handling the case, Sierra Leone health ministry spokesman Sidi Yahya Tunis said that the patient had been tested for the virus and had received treatment in a government hospital. He did not give further details.

Information campaigns calling upon residents of Ebola-affected countries to respect government health directives have been largely credited with turning the tide of the epidemic. However, safety measures, particularly a ban on traditional burial ceremonies, have faced stiff resistance at times.

The report stated that five people who were not part of Jalloh’s parents’ household were involved in washing her corpse, a practice that is considered one of the chief modes of Ebola transmission.

Almost all the victims of the regional epidemic, which originated in the forests of Guinea in 2013, were in Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia.

As of Thursday’s WHO announcement that Liberia had gone 42 days with no new cases, all three nations were apparently Ebola-free.

But Liberia had twice been given the all-clear last year, only for a fresh cluster of cases to emerge. And the case in Sierra Leone adds further uncertainty.

“It is really important that people don’t understand this 42-day announcement as the sign that we should all just pack up and go home,” WHO spokesman Tarik Jasarevic said on Friday. “We should stay there and be ready to respond to these possible cases.”

Ben Neuman, an Ebola expert and lecturer in virology at Britain’s University of Reading, said: “A hospital in Sierra Leone completely misdiagnosing a case of Ebola, apparently without sending a sample to one of the many testing labs that are being kept open for just this reason is ridiculous -completely unacceptable.”

He said Ebola was hard to distinguish from many other diseases that cause pain, fever, diarrhea and vomiting.

“The only way to know for sure is by testing whether pieces of the Ebola virus are present in the blood,” Neuman added.

“People still make better doctors and nurses than computers, but people will always make mistakes. Unfortunately this mistake is a big one.”

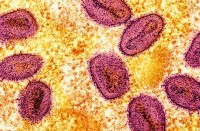

Ebola is passed on through blood and bodily fluids, and kills about 40 percent of those who contract the virus.

While the WHO has said that another major outbreak is unlikely, it says the risk of flare-ups remains because of the way the virus can persist in those who survive it. Research on survivors has located it in semen, breast milk, vaginal secretions, spinal fluid and fluids around the eyes.