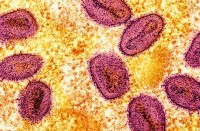

Salim al-Jabouri (R), speaker of the Iraqi Council of Representatives, and Haider Abadi (L), a member of Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki’s State of Law bloc, speak during a news conference in Baghdad, July 15, 2014.

Credit: Reuters/Ahmed Saad

BAGHDAD

(Reuters) – Pressure on Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Maliki to step aside had become unbearable. Sunnis, Kurds, fellow Shi’ites, regional power broker Iran and the United States all wanted him out.

Maliki calculated he may have one more chance to hold onto power after eight years in office, even though alarmed allies had run out of patience as Islamic State jihadis swept government forces aside in much of western and northern Iraq.

Maliki’s plan would require persuading Iraq’s most influential cleric that he alone could reform and unite a country that had slid back into a civil war fueled by what critics view as his sectarian politics.

A week ago, he sent a delegation from his Islamic Dawa Party to try to meet Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani in the sacred Shi’ite city of Najaf, south of Baghdad, according to an Iraqi minister and a source close to the clergy.

It was unclear if they succeeded in gaining an audience with the reclusive 83-year-old cleric, but they did get a response on paper, if not the one that Maliki was hoping for:

“Sistani made it clear that he wanted change. He put it in writing – the first time that a leader of Iraq’s Shi’ite clergy did such a thing,” the minister told Reuters.

Sistani’s word is law in majority Shi’ite Muslim Iraq so the fate of Maliki – an unknown when he first came to power in 2006 with help from Iraq’s then U.S. occupiers – was sealed.

Maliki has been caretaker prime minister since an inconclusive parliamentary election in April. But his chances of a third term appear over, with a party colleague named as prime minister-designate and drawing endorsements from home and abroad.

While Maliki kept digging in, the main Iraqi and foreign players moved on to wondering who could replace him.

Several names came up. One was Ahmad Chalabi, the smooth-talking, secular Shi’ite who played a role in persuading the United States to topple Sunni dictator Saddam Hussein in 2003.

Maliki’s immediate predecessor Ibrahim al-Jaafari was also a candidate. But he had failed to ease sectarian violence during his year in office. Deputy Prime Minister Hussain al-Shahristani, a nuclear scientist tortured in Saddam’s jails, seemed promising, people familiar with the discussions said.

A SAFE CHOICE

But, officials said, in the end it came down to a choice between Vice President Khudhaier al-Khuzaie and former Maliki lieutenant Haider al-Abadi, a deputy speaker of parliament. Both were also members of Maliki’s Dawa Party but Khuzaie was seen as too sectarian, too like Maliki in that regard.

Abadi was selected because all parties agreed the low-key figure got along with leaders of the Kurdish minority and had a decent chance of appeasing Sunni Muslims, whose disgust with Maliki prompted some to join the Islamic State militants.

Abadi also appealed to religious leaders and others because the engineer appears not to be motivated purely by political ambition. He spent more than two decades in exile, working in business in Britain while promoting the Islamic ideals of the Dawa party.

“Everyone decided enough is enough. Maliki was turning Iraq into a dictatorship and ruining its democracy. People were losing patience. This came to a head when the Islamic State invaded,” said Haqim al-Zamili, a parliamentary ally of the influential Shi’ite cleric Moqtada al-Sadr.

“The clergy made their point in Friday sermons. They sent representatives to Baghdad – to pressure Shi’ites to push for change.”

Abadi returned to Iraq after the fall of Saddam, who had had two of his brothers executed. He eventually served as an adviser to Maliki as premier and telecommunications minister.

The decision to select Abadi was also based on a desire by all parties for a successor who would not remain in thrall to Maliki. While in office Maliki placed loyal allies in influential positions in all the main institutions of state.

Abadi fit the bill – a member of Dawa but not part of Maliki’s inner circle so the selection would neither alienate a core Shi’ite constituency nor, they hoped, simply give Maliki the chance to remain the power behind the throne.

Aside from marginalising the Sunnis and infuriating the Kurds by challenging their long-standing dream of independence, Maliki’s mistake was to alienate fellow Shi’ites, especially his long-time ally Iran.

Abadi is not seen as a forceful figure who can antagonise, so he appealed to everyone from leaders in Tehran and the top clergy on Najaf to Sunni cities and towns where the Islamic State has capitalised on anti-Shi’ite resentment.

Maliki had become so divisive, that some feared he would provoke a conflict among Shi’ites, further fragmenting the country.

After Muslims celebrated the end of the fasting month of Ramadan in late July, the Najaf religious powers sent a letter to Abadi through Shi’ite lawmaker Abdul Hadi al-Hakim encouraging him to accept the nomination of prime minister. He accepted.

“Abadi was selected by the Shi’ites and also approved by the clergy as he was not from Maliki’s tight circle. This means no way Maliki could control him in future,” said an member of parliament from the main Shi’ite coalition. “Abadi was most acceptable for all parties, including Sunnis and Kurds. That would definitely help to smooth the sectarian tension that emerged.”

OLD FRIEND IRAN SHIFTS POSITION

Even Maliki’s long-time supporter Iran decided it was time to part ways and start looking for an alternative.

Like its enemy the United States, Iran had been closely watching the Islamic State’s advances in northern Iraq, fearful at the prospect of violence spilling over the border.

A senior Iranian official said Iranian and American officials held discussions on who could rescue Iraq, a major oil exporter. “Iranians and Americans held talks over possible candidates and after at least three sessions, they agreed on Abadi,” said the official.

“He is Shi’ite and given the sensitivity of the situation in Iraq and desperate need to create a united front, Iran agreed to convince Shi’ite groups to support Abadi. Some Iranian clerics based in Najaf were involved and lobbied for him.”

A U.S. official denied Washington, which has launched air strikes on the Islamic State militants, had tried to push Abadi into power, saying his name had come up through the Iraqi political system.

“It’s not like we were leading this charge,” said the official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The Saudis, the others who are active in the region, basically said ‘we are not going to do anything for Iraq if Iraq is not going to do something for itself.’ They had basically had it with Maliki.”

Another Iranian official said Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei had signed off on Abadi after long discussions with a group of seven advisers.

“Abadi for the time being is a good choice and we have also talked to various Shi’ite groups in Iraq and hope he will be successful,” said a high-ranking Iranian official.

The Iraqi minister said Sistani had contacted Iran’s supreme leader weeks ago to set the groundwork for a new prime minister. “He asked Iran to accept the Iraqi people’s choice for a leader and the Iranians agreed,” said the minister.

Sistani, who favours a behind-the-scenes role, called on Iraqis to take up arms against the Islamic State. Like many Iraqis, he feared sectarian tensions would play into the hands of the Sunni jihadis who believe the majority Shi’ites are infidels who should die.

Using Friday sermons, Sistani repeatedly urged Iraqi leaders to stop clinging to their posts – a clear reference to Maliki, who drew comparisons with Saddam Hussein, the man he plotted against for years from exile.

Behind the scenes he also used his weight to push Shi’ite politicians to ditch Maliki. Saying no to a man who is revered by millions of Iraqis is not an option.

The Shi’ite politicians caved in and sent a delegation to see Sistani three weeks ago to ask for more specific directions, according to members of the main Shi’ite coalition.

“This was not easy, it was a very difficult mission. We became really embarrassed and under pressure from the religious establishment,” said a Shi’ite politician who pushed for Abadi. “The clergy kept on pressuring us. So it became a must for us. This was beyond politics; it became a duty.”

In the end Sistani’s tough stand plus a swirl of pressures – including the fear of the Islamic State gaining more Sunni followers and making good on its threat to march to Baghdad – prompted six members of the main Shi’ite coalition to act.

They held a meeting and formally agreed on Abadi, whose favourite quotation according to his Facebook biography is “the key to leadership is tolerance”.

“We drafted the decision and signed it,” said one of the members of the National Alliance. They then handed it to President Fouad Masoum who immediately appointed Abadi.

Now millions of Iraqis, the United States, Iran and other regional powers such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey will be watching to see if he is the man who can contain the Islamic State, and end the daily kidnappings, bombings and execution killings.

As for Maliki, he has dire predictions for a country whose very survival as a unified state is in jeopardy. “I have been speaking with Maliki. He is worried. He believes Iraq will be a failed state, a nation of militias,” said Salam al-Maliki, a prominent sheikh in the former prime minister’s tribe.

(Additional reporting by Ahmed Rashid and Raheem Salman in Baghdad, Parisa Hafezi in Ankara and Mariam Karouny in Beirut, Arshad Mohammed in Washington; editing by David Stamp)