by Sunghee Hwang

Agence France-Presse

SEOUL, South Korea (AFP) — Born into an elite North Korean family with ties to the ruling dynasty, Oh Hye Son grew up believing she was “special” — but then she tasted freedom overseas and decided to defect.

Most of the tens of thousands of North Koreans who have escaped repression and poverty at home make an arduous, high-risk journey across the country’s land border with China, where they face arrest and possible deportation.

Oh’s family’s defection was less dangerous but equally as wrenching: she convinced her husband Thae Yong Ho, then deputy ambassador at North Korea’s London embassy, to give up their privileged place in the Pyongyang regime for the sake of their children.

“I wanted to never return to North Korea and questioned why North Koreans had to live such a hard life,” she told AFP in an interview in Seoul, where she now lives.

Years of postings across Europe — in Denmark, Sweden, and Britain — exposed the family to a different life, she said, adding that when she first arrived in London she thought: “If there is paradise, this must be it”.

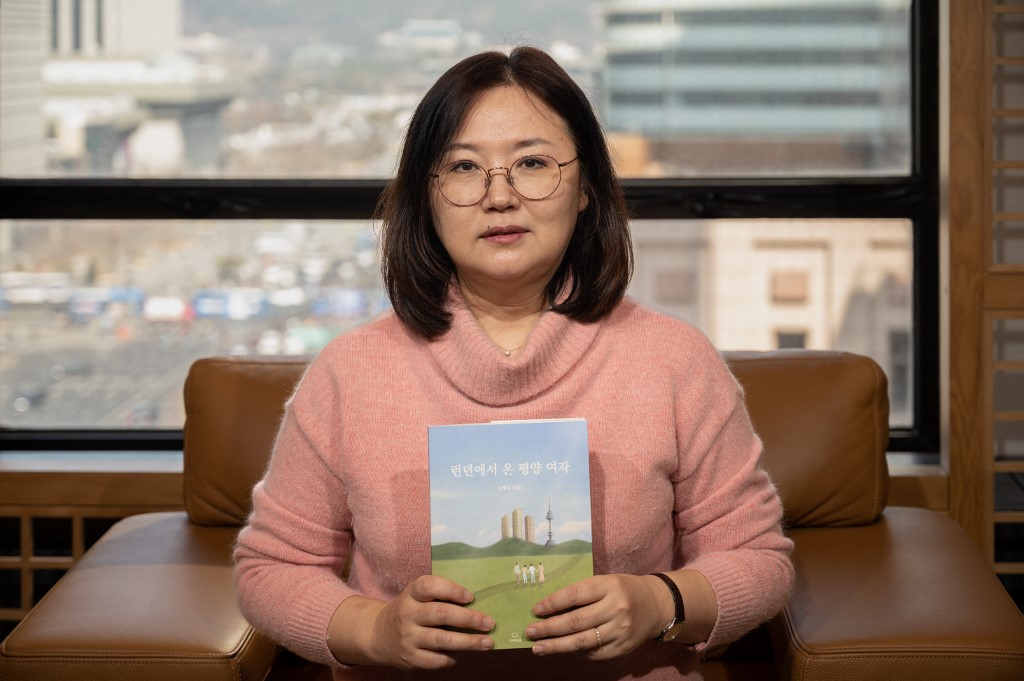

Oh, who recently published a Korean-language memoir, was once part of Pyongyang aristocracy — a descendent of a famed North Korean general who fought alongside leader Kim Il Sung against the Japanese in the 1930s.

But despite this impeccable pedigree, she still “lived in fear of power”, she said.

“No one except the Kim family had privileges, and as my children learned about freedom and democracy when they lived abroad, I realized there was no future for them in North Korea,” she added.

– NHS love –

Oh’s eldest son Thae Juhyok had chronic health problems including nephrotic syndrome, a condition which can cause life-threatening kidney problems if not treated.

Getting that treatment was near impossible in Pyongyang’s crumbling health system — one of the world’s worst — where doctors had to be bribed to do anything and crucial medicines were lacking.

Oh said it was eye-opening when the family first arrived in London in 2004 and became eligible for the National Health Service.

Her son was soon able to get free treatment at one of the best medical facilities in the city, she said, adding that her children also went to British schools, where they settled in well.

“The children grew up so bright in England, in a society that respected them,” she said.

It was a stark contrast to life in Pyongyang, to which they returned in 2008 after her husband’s first London posting ended.

Juhyok attended the Pyongyang Medical University, but instead of studying he was put to work on a construction site hauling cement, Oh said.

North Korea is beset by labor shortages across economic sectors and it is common for the government to order students, even schoolchildren, to do manual labor as a demonstration of loyalty.

If one fails to comply, the government reportedly withholds food rations or imposes taxes, according to a 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report published by the US State Department.

As her overseas-raised children began questioning the corruption and injustice they observed in North Korea, Oh realized it would be impossible for them to fully integrate into Pyongyang society.

“They had completely different values,” she said.

“It was then that I began thinking that if I ever had a chance to go overseas again, I will not return.”

– Escape –

Oh’s chance came when her husband was again posted to London as the deputy ambassador, and she convinced him to defect as she did not want to be “resented by her children in the future”.

She had hoped the North Korean regime would collapse after the death of Kim Jong Il, the father and predecessor of current leader Kim Jong Un, and was crushed when his son emerged as the third generation of Kims to rule.

“In North Korea, you existed — from morning to night — for the sake of the Kim family,” Oh said.

Thae became the first defector to be elected to South Korea’s parliament, where he is now a high-profile lawmaker for the conservative People Power Party.

Oh loves her new life in Seoul, but is haunted by thoughts of her mother and siblings left behind in North Korea, which is known to punish defectors’ family members.

She can’t check in with them: civilian contact is banned between the two Koreas, although some defectors have used intermediaries to smuggle Chinese mobile phones across the border.

Oh has not managed to contact her family, but she once glimpsed her brother-in-law when he was part of an official North Korean delegation that visited Seoul in 2018 during a rare bout of diplomacy.

It gave her hope that her relatives had not been purged by the Kim regime as a result of her family’s escape.

“Will they resent me? Will they envy me? Or will they silently cheer for me?” she said, wiping away tears.

© Agence France-Presse