HAWAII, United States (Reuters) — Surveys of ocean areas where floating plastic accumulates, such as the North Atlantic gyre, have found far less plastic than expected, perhaps less than a tenth as much.

A mathematical formula developed by Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona researchers Blai Vidiella and Nuria Conde could not explain the trend, but the pair believes a population boom in microbes that evolved to biodegrade plastic is the explanation.

Conde told Reuters: “What is clear is that all microbes have the capacity to evolve and the species that is able to take the plastic as a food resource has a great advantage on the other ones and that’s why they can increase in number.”

According to Vidiella, “in the future we expect that plastic input will increase at the same rate because humans are creating more plastic and there’s a lot of plastic in landfills that will be passively going to the ocean.”

“But we expect that microbes will continue eating this plastic and maintain the observable and measurable plastic constant,” Vidiella added.

However, the evolution of plastic-eating microbes might not be an entirely positive outcome.

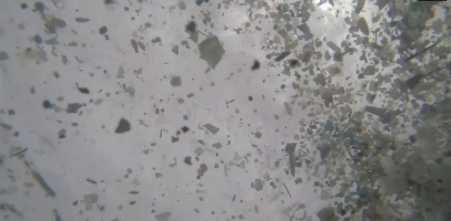

Conde said: “Since these microbes can destroy the plastics we have micro, micro, plastics so tiny that you need a microscope to look at them. That means that all the ecosystems, all the organisms in the food chain can eat plastics, from those that are invisible to whales. Everybody could be eating plastics.”

In a separate study, environmental chemist Alexandra ter Halle, of the Laboratoire des IMRCP, said that additives within plastics could be released and enter the food chain if the plastic part biodegrades.

Linda Amaral-Zettler, of the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research, suggested that floating plastic might be simply sinking to the seafloor or breaking into microscopic pieces that slip through the nets of research vessels.

Plastics are being found in the stomachs of seabirds and turtles, which can then starve to death.

A 2006 Greenpeace report, “Plastic Debris in the World’s Oceans” said at least 267 species — including seabirds, turtles, seals, sea lions, whales and fish — are known to have suffered from entanglement or ingestion of marine debris.

Small crustaceans called amphipods, which populate the deepest recesses of the Pacific, were found to contain disturbingly large levels of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in the organism’s fatty tissue.

Amphipod samples brought to the surface contained chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), commonly used as electrical insulators and flame retardants. Use of the former was banned in the 1970s.

The authors believe the pollutants were probably transported to the trenches through contaminated plastic debris and dead animals sinking to the bottom of the ocean.

These are often consumed by amphipods and other fauna, which are then eaten by larger fauna, beginning their journey up the food chain.