STOCKHOLM, Sweden (Reuters) — Swedish scientists have discovered that the malaria parasite in infected humans sends out a signal to attract mosquitoes to feed from them and continue the cycle of infection.

Together with their colleagues, Professor Ingrid Faye of the Department of Molecular Biosciences and Noushin Emami, post-doctoral researcher at the Wenner-Gren Institute at Stockholm University, discovered that the system helps the malaria parasite to spread and survive without killing the hosts.

In a laboratory at Stockholm University, the scientists experimented by feeding mosquitoes with infected and uninfected blood.

“I always see when I offer the infected blood to mosquitoes that they are faster (to feed). After that I discussed with my mentor Ingrid Faye, and I just explained that my understanding depends on this system,” Emami explains.

“She offered me (the chance to) prepare a test for that, and then I make it. I discovered that, yes, it’s really fast – 90 seconds, all the mosquitoes come and are really fed and completely engorged and fly away.”

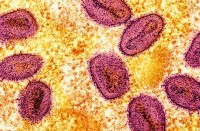

The parasite produces a molecule called HMBPP, which stimulates human blood to release more carbon dioxide, making the blood more attractive to mosquitoes and causing them to eat more.

“The interesting thing was that when we took away the red blood cells from the blood and just gave them serum with this molecule, they didn’t care, so it was the same with the control and the actual test, which was really interesting,” Faye explained.

“From that we could go on and find out that it was the red blood cells that are activated or inducing the release of certain smells or volatiles that, in addition to carbon dioxide, attracted the mosquitoes.”

Mosquitoes were previously thought to randomly collect the malaria infection and pass it on by biting uninfected hosts.

“For a long time we have known that malaria in the field is transmitted between infected and uninfected people,” Noushin Emami said.

“Most people think that it is by chance that mosquitoes go and bite people infected with the malaria parasite, and get the parasite. Then, next time they bite another person they can then transfer the parasite to the next person. But we understand that no, this is not by chance – the parasite makes a signal for its own transmission. And if we can just disrupt these signals, maybe we can disrupt the cycle of malaria after this long, long time,” Emami added.

The scientists say they are now researching ways to combat malaria by disrupting the transmission of signals, thus breaking the cycle of infection.

“The mosquitoes like to bite the infectious person, we trap the mosquitoes, then we control the system, and trapping could be the best and the first idea for us,” Emami said.

The research was published in the journal Science.