By Callum PATON

OMAGH, United Kingdom, Aug 11, 2023 (AFP) – On a bright Saturday in August almost 25 years ago, Kevin Skelton was rejoining his family shopping for new school shoes in Omagh’s town centre when a massive bomb went off.

Amid the ensuing carnage, he clambered through a hole in the shop’s storefront trying to reach his wife Philomena and their three girls.

“I found Mena lying face down in the rubble,” said Skelton, who recalled checking her for a pulse. “I could find nothing.”

Philomena, who was aged 39, was one of 29 people killed when the car bomb planted by the Real IRA exploded next to the shop on August 15, 1998. The dead included two unborn twins.

Skelton’s daughter Shauna was among the more than 200 people who were injured, while his other two girls escaped physically unscathed.

It was the deadliest attack in three decades of violence in Northern Ireland known as “The Troubles”.

Skelton is still haunted by the apocalyptic scene and “the cries of pain” as he searched for his family that day.

“What in God’s name was it all for?” the 68-year-old asked.

Although Northern Ireland has remained largely peaceful during that time, he fears a similar attack by paramilitary groups, which are vastly diminished but remain a serious threat.

“You always have that fear. You only need one lunatic to put a bomb in the boot of a car… and park it in a main street and walk away,” Skelton told AFP.

– ‘Galvanising effect’ –

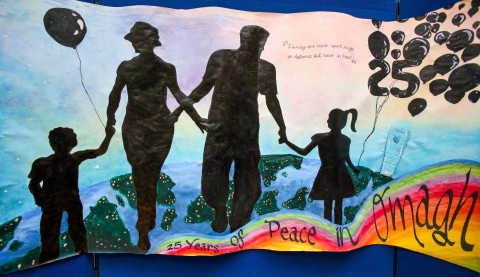

The Omagh bombing came four months after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, which aimed to end “The Troubles”.

It was perpetrated during an IRA ceasefire by dissident Republicans opposed to the deal.

“Despite that terrible tragedy, it actually had a galvanising effect on the peace process because it came so soon after the Good Friday Agreement,” Queen’s University Belfast academic Peter McLoughlin said.

But the political historian noted “hardcore” remnants remain within both pro-UK loyalist and pro-Ireland republican communities, with police noting around a third of organised crime is also directly linked to paramilitaries.

“There will always tend to be groups who have this extreme position, that violence is the way forward and will try and exploit the political difficulties,” McLoughlin said.

Northern Ireland has been without a devolved government for much of the past six years, amid multiple breakdowns in power-sharing between the two communities.

Loyalist paramilitaries — namely the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and Ulster Defence Association (UDA) — number an estimated 12,500, according to information provided to the BBC by Northern Irish police and Britain’s MI5 domestic intelligence agency.

The New IRA, the most prominent dissident Republican paramilitary group, is far smaller, with merely dozens of members.

Despite its size, it has carried out several high-profile attacks in recent years.

In April 2021, the group planted a bomb by a policewoman’s car in what police called an attempt to kill her and her daughter.

In February, the group shot John Caldwell, a senior police officer in Omagh, as he left a sports complex with his son while off-duty.

Shortly afterwards, the UK government raised Northern Ireland’s terrorism threat level, citing the continuing threat of political violence.

– ‘No right’ –

The attacks have heightened deep unease within Northern Irish police over their vulnerability, made worse by two separate data leaks announced this week which revealed the personal details of thousands of staff.

The last police officer killed by dissident Republicans was Ronan Kerr. A bomb was placed under his car and exploded outside his home in Omagh in 2011.

Meanwhile the civilian population has been left scarred by the decades of violence, with 15 to 30 percent of people impacted by “paramilitary harm”, according to official estimates.

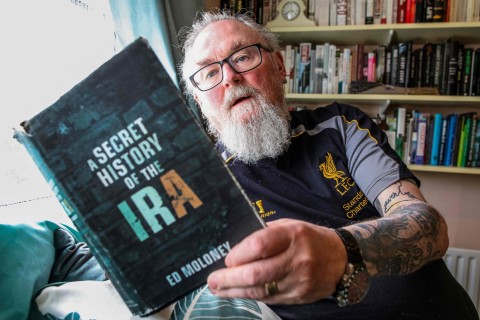

Anthony McIntyre, a former Provisional IRA gunman, was jailed for 18 years for the 1976 killing of a UVF member.

Released from prison in 1992 and now a writer and academic, he initially continued to support the IRA’s bombing campaign but by the 1998 Omagh attack had renounced violence.

“I was appalled by it,” he said. “We simply had no right.”

McIntyre joined the IRA in 1973 because of “events on the street, British Army harassment, loyalist killings”, but also because “it seemed romantic”.

He rejects today’s New IRA as a “cult”, arguing that acts like Caldwell’s assassination attempt have “appalling logic”.

“The people who came to kill John Caldwell weren’t doing anything at all other than trying to introduce mayhem as part of a failed military and political struggle,” McIntyre said.

And to do that in Omagh, in particular, was like “visiting the scene of the crime to desecrate it,” he added.