By Daniel Lawler

One in 10 premature births in the United States have been linked to pregnant women being exposed to chemicals in extremely common plastic products, a large study said on Wednesday.

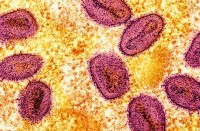

The chemicals, called phthalates, are used to soften plastic and can be found in thousands of consumer items including plastic containers and wrapping, beauty care products and toys.

Phthalates have been known for decades to be “hormone disruptors” which affect a person’s endocrine system and have been previously linked to obesity, heart disease, some cancers and fertility problems.

Because they affect hormones, these chemicals “can precipitate early labour and early birth”, lead study author Leonardo Trasande of New York University’s Langone Health centre told AFP.

By analysing the level of phthalates in the urine of more than 5,000 pregnant women in the United States, the researchers were able to examine how exposure to the chemicals could have affected how early the babies were born.

The 10 percent of mothers with the highest levels of phthalates had a 50-percent increased risk of giving birth before week 37 compared to the lowest 10 percent, according to the study in The Lancet Planetary Health.

Extrapolating their findings across the US, the researchers said that nearly 56,600 preterm births could have linked to phthalate exposure in 2018 alone, roughly 10 percent of the country’s premature births that year.

Babies born prematurely or at a lower weight tend to have more health problems later in life.

The researchers estimated the resulting medical and social costs of phthalate exposure for preterm births in the United States was between $1.6 and $8.1 billion.

While the study was carried out in the US, Trasande said that phthalates are so ubiquitous that five to 10 percent of premature births in most other countries could probably be linked to the chemicals.

– How to avoid phthalates –

He estimated that more than three quarters of exposure to phthalates was due to plastic.

Trasande said the benefits of plastic to society need to be weighed against its harms, calling for a global treaty to dramatically reduce plastic production.

“The people who are producing plastic are not paying for the health effects. They’re not caring for these preterm babies,” he said.

As awareness has grown about the potential threat posed by the common phthalate DEHP, some plastic companies have tried replacing it with other compounds from the chemical group.

“What was even more frightening” about the new study was that these “replacement phthalates were associated with even stronger effects than DEHP”, Trasande said.

He called for phthalates to be regulated as a group, rather than focusing on specific compounds.

Stephanie Eick, a reproductive health researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved in the study, said the research could not prove definitively that the premature births were directly caused by phthalates.

But there are now an “overwhelming number of observational studies that support this hypothesis”, she told AFP.

To avoid exposure, Eick advised people to eat less food wrapped in plastic and avoid personal care products that contain phthalates.

Trasande warned that putting plastic containers in microwaves or dishwashers can bring out phthalates, allowing them to later absorb into food.