by Sara HUSSEIN

TOKYO, Japan (AFP) — A new method to create insulin-producing pancreatic cells from stem cells and protect them from the body’s immune system could pave the way for improving experimental diabetes treatment.

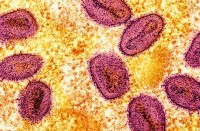

In type-1 diabetes, the body turns on itself and attacks the so-called beta cells inside clusters in the pancreas called “islets”.

These beta cells are responsible for gauging sugar levels in the blood and releasing insulin to keep them stable. When they are depleted, a person is at risk for either high or low blood sugar and has to rely on insulin injections.

One treatment devised to end that reliance involves transplanting donor islets into diabetics, but the process is complicated by several obstacles.

There are not enough donors, especially as one transplant generally requires several to ensure enough islets are available.

Islets also often fail to connect with blood supply, and even when they do, like other transplants, they risk attack from the immune system of the recipient, which sees it as an invasion.

As a result, patients have to take drugs that suppress their immune systems, protecting their transplant but exposing the rest of their body to other illness.

In a bid to overcome some of these challenges, a team looked to find another source for islets, by coaxing induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS) to produce what the team called HILOs, or human islet-like organoids.

These HILOs, when grown in a 3D environment mimicking the pancreas and then turbocharged with a “genetic switch”, successfully produced insulin and were able to regulate blood glucose function after being transplanted into diabetic mice.

Fending off immune attack

Having found a potential way to solve the supply chain problem, the scientists then sought to tackle the issue of immune rejection.

They focused on something called PD-L1, a kind of protein that is known to inhibit the body’s immune response.

When the team induced the HILOs to produce PD-L1, they were effectively able to “hide” the transplants from the body’s immune system, protecting them from attack.

They transplanted HILOs both with and without PD-L1 into diabetic mice to test the function.

Initially, both transplants worked to restore control of blood glucose levels, but gradually, the unprotected HILOs stopped functioning.

But the HILOs with PD-L1 continued to help the diabetic mice regulate their blood glucose for more than 50 days.

“This is the first study to show that you can protect HILOs from the immune system without genetic manipulation,” said Michael Downes, senior staff scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and a co-author of the study published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

“If we are able to develop this as a therapy, patients will not need to take immune-suppressing drugs,” he added in a statement issued by Salk.

Around 422 million people worldwide were living with diabetes by 2014, according to the World Health Organisation, a figure that includes both type-1 and type-2 diabetes.

Islet transplantation is generally considered as a treatment for type-1 diabetics, whose disease is the result of an auto-immune response.

But while the prospect of individually grown islets derived from stem cells might appear an attractive solution, the study warns that is likely to be “prohibitively expensive.”

A more likely application of the research might be to use the PD-L1 protection method to allow successful transplants without the need for immunosuppressants, the authors wrote.

© Agence France-Presse