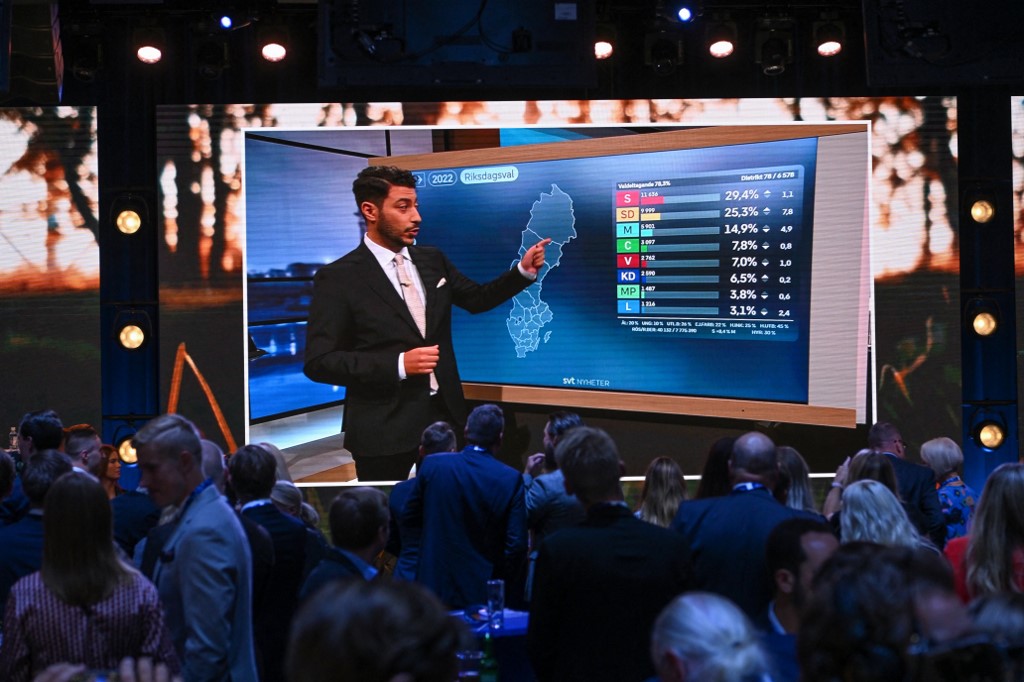

STOCKHOLM, Sweden (AFP) – Sweden’s right wing looked set to oust Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson’s left-wing bloc in Sunday’s general election on strong gains by the far-right, clinging to a slim lead with 94 percent of electoral districts counted.

The right wing bloc was credited with a majority of 176 of 349 seats in parliament, with the left bloc trailing with 173.

With the vote deemed too close to call, election authorities said they did not expect a final result until Wednesday when the last ballots from abroad and from advance voting had been counted.

“We’re not going to have a final result tonight”, Andersson, 55, told her cheering supporters as the outcome hung in the air, calling on Swedes to “have patience” and “let democracy run its course”.

Andersson’s challenger Ulf Kristersson of the conservative Moderates and the leader of the right-wing bloc, said that while the election results could still change, “I am ready to build a new and strong government”.

The Moderates and two other smaller right-wing parties have for the first time tied up with the anti-immigration and nationalist Sweden Democrats, which looked set to post their best election score yet.

The far-right party, which entered parliament in 2010 with 5.7 percent of votes and have long been treated as “pariahs” by other political parties, was seen garnering around 20.7 percent of votes.

That makes them the country’s second-biggest party for the first time, overtaking the Moderates, the traditional leaders on the right.

The election campaign was dominated by issues close to right-wing voters and especially the far-right, including rising gang shootings, immigration and integration issues.

While Andersson’s Social Democrats looked set to remain the country’s biggest party with 30.5 percent, the Moderates slipped to third position, at 19 percent.

That is a setback for Kristersson, who orchestrated a major shift in Swedish politics by initiating exploratory talks in 2019 with the Sweden Democrats.

The two other small right-wing parties, the Christian Democrats and to a lesser extent the Liberals, later followed suit.

– ‘Looking good now’ –

“Our goal is to sit in government. Our goal is a majority government,” Sweden Democrats party leader Jimmie Akesson told a crowd of cheering supporters on Sunday evening.

“It’s looking pretty damn good now”, he said.

Party secretary Richard Jomshof told public television SVT he “didn’t believe” other parties would be able to freeze out the Sweden Democrats again and expected to have a strong influence on the country’s politics.

“We are so big now… it is clear we should have a spot on parliamentary committees”, he said.

He said the party had “a chance to be an active part of a government that would move politics in a completely different direction”.

Prime Minister Andersson, a former finance minister, campaigned on building a government with the support of the small Left, Centre and Green parties.

The Social Democrats have governed Sweden since 2014 and dominated the political landscape since the 1930s.

“We Social Democrats have had a good election”, she told party members late Sunday, adding: “Swedish Social Democracy stands strong”.

– ‘Enormous shift’ –

Both blocs are beset by internal divisions that could lead to lengthy negotiations to build a coalition government.

On the right wing, the Liberals have said they are opposed to the Sweden Democrats being given cabinet posts, political scientist Katarina Barrling noted.

They would prefer for the far-right to remain in the background providing informal support in parliament.

But for a number of reasons there is “pressure to have a united and effective government” in place quickly, she said.

Sweden faces a looming economic crisis, is in the midst of a historic NATO application process and is due to take over the EU presidency in 2023.

The end of the Sweden Democrats’ political isolation, and the prospect of it becoming the biggest right-wing party, is “an enormous shift in Swedish society”, said Anders Lindberg, an editorialist at left-wing tabloid Aftonbladet.

Born out of a neo-Nazi movement at the end of the 1980s, the party’s rise has come alongside a large influx of immigrants. The country of around 10 million people has taken in almost half a million asylum seekers in a decade.

It also comes as Sweden struggles to combat escalating gang shootings attributed to battles over the sale of drugs and weapons.

Crime was one of far-right voters’ top concerns.

jll-bur/po/it

© Agence France-Presse