BY LISA MARIA GARZA

(Reuters) – Up to 100 people may have had contact with the first person diagnosed with Ebola in the United States, and four people were quarantined in a Dallas apartment where sheets and other items used by the man were put in sealed plastic bags to prevent infection.

Health officials said on Thursday that 12 to 18 people had direct contact with the patient, who flew to Texas from Liberia via Brussels and Washington two weeks ago, and they in turn had contact with scores of others.

None of those thought to have had contact with the patient, Thomas Eric Duncan, were showing symptoms of Ebola, Dallas County officials said at a news conference. Duncan had been staying in an apartment in the northeastern part of the city for about a week before going to a Dallas hospital.

“The sheets were placed in a sealed plastic bag and have been in the bag, as well as the belongings of Mr. Duncan, those were also in a bag,” said Clay Jenkins, Dallas County’s top political official.

Ebola can cause fever, bleeding, vomiting and diarrhea and spreads through contact with bodily fluids such as blood or saliva. It has killed at least 3,338 people in Liberia and two other impoverished West African countries, Guinea and Sierra Leone, in the worst such outbreak since the disease was identified in 1976.

In Liberia, the head of the country’s airport authority, Binyah Kesselly, said the government could prosecute Duncan for denying he had contact with someone who was eventually diagnosed with Ebola.

The government said Duncan failed to declare that he helped neighbor Marthalene Williams after she fell critically ill on Sept. 15. Williams died.

Kesselly said Duncan was asked in a questionnaire whether he had come in contact with any Ebola victim or was showing any symptoms. “To all of these questions, Mr. Duncan answered ‘no,'” Kesselly said.

Officials have said the U.S. healthcare system is well prepared to contain the hemorrhagic fever’s spread by careful tracking of those who have had contact with Duncan, and employing appropriate care.

Dallas County officials said the problem was very localized. “When I say local, I don’t mean Dallas. I mean a very specific neighborhood in the northeast part of Dallas,” Mayor Mike Rawlings told reporters.

HOSPITAL SENT PATIENT AWAY

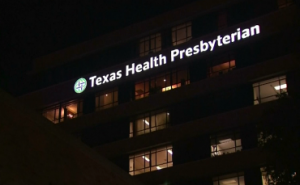

Duncan initially sought treatment at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital on the night of Sept. 25 but was sent back to the apartment, with antibiotics, despite telling a nurse he had just been in Liberia. By Sunday, he needed an ambulance to return to the same hospital after vomiting on the ground outside the apartment complex.

He was in serious condition on Thursday, no change from Wednesday, a hospital spokeswoman said.

Police and armed security guards were keeping people about 100 yards (meters) away from the apartment, with orange cones blocking the entrance and exit. Maintenance workers scrubbed the parking lot with high-pressure water and bleach.

Dr. David Lakey, commissioner of the Texas Department of State Health Services, said the four people under quarantine did not have a fever and were healthy.

Lakey said monitoring included fever checks twice a day. At the apartment, “there is a law enforcement person there in case individuals leave,” Lakey told reporters on a conference call.

U.S. officials initially described the number of people potentially exposed as a handful, and on Wednesday said it was up to 18. Then on Thursday, the Texas health department said there were about 100 potential contacts.

CNN reported that a Dallas woman who had a child with Duncan said he had sweated profusely in the bed they shared at her apartment. The woman, whom CNN identified only as “Louisa,” is quarantined in the apartment with one of her children, who is 13, and two visiting nephews in their 20s (Health officials described them as relatives of Duncan.)

They were all in the home when Duncan began showing signs of illness, the report said. The woman said she mentioned twice to hospital staff that he had come from Liberia.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) director, Dr. Thomas Frieden, told reporters on Thursday that the agency had interviewed most of the 100 people who may have had contact with Duncan and “there are a handful who may have had exposure and who therefore may be monitored.”

Dr. Amesh A. Adalja, an infectious disease physician at the University of Pittsburgh, said contact tracing is “bread-and-butter public health,” and something health officials do regularly to track tuberculosis, measles and sexually transmitted diseases.

Adalja said the most disturbing part of the U.S. incident is that Duncan was sent home from the hospital with antibiotics.

“This really is something that shouldn’t have happened,” he said. “It just reinforces that taking a travel history has to be an essential part of taking care of patients.”

(Reporting by Susan Heavey, Doina Chiacu and Toni Clarke in Washington, Colleen Jenkins in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Jon Herskovitz in Austin, Lisa Maria Garza and Marice Richter in Dallas, Jim Forsyth in San Antonio and Brendan O’Brien in Milwaukee; Felix Bate in West Africa; Writing by Jim Loney and Grant McCool; Editing by Bernadette Baumand Jonathan Oatis)